Well, are you a fan of “The Simpsons”? I am – particularly seasons 1 through 10. In the season finale of season 8, an episode called “The Secret War of Lisa Simpson,” Bart is sent to a military school to be disciplined; Lisa – who finds her public education to be unfulfilling – seeks a challenge and enrolls with him; however, she faces discrimination as the school's only girl cadet.

At the school, Lisa is isolated in her dormitory, and she begins to feel depressed.

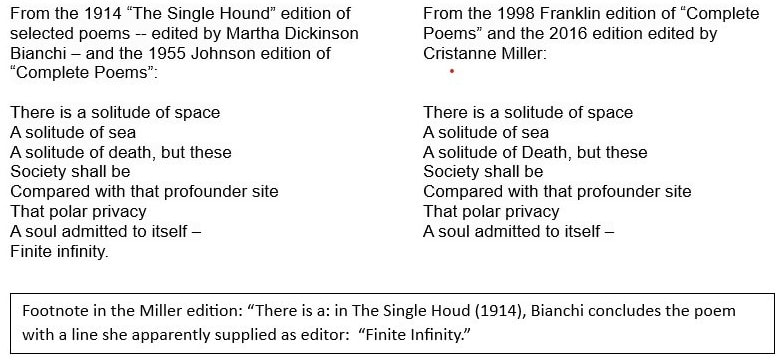

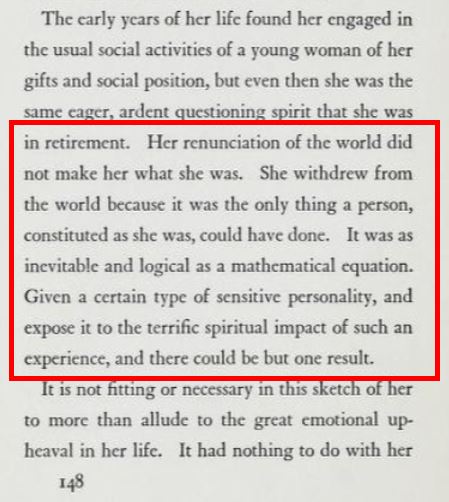

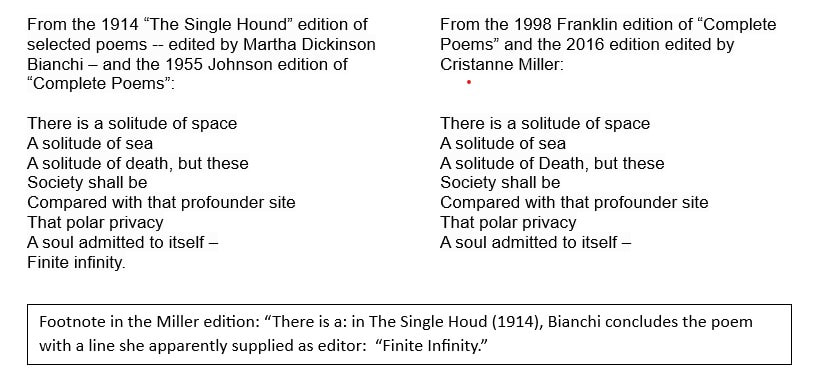

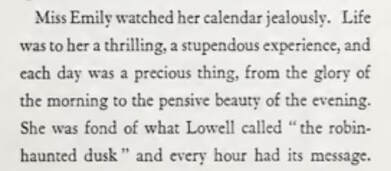

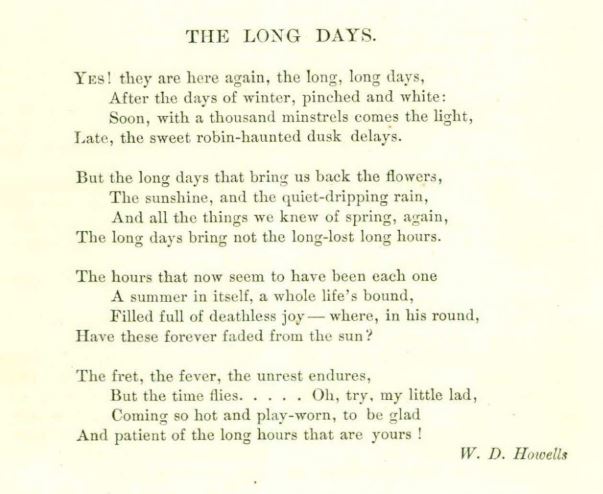

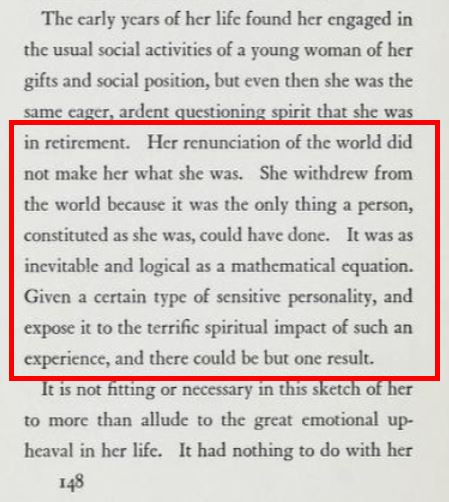

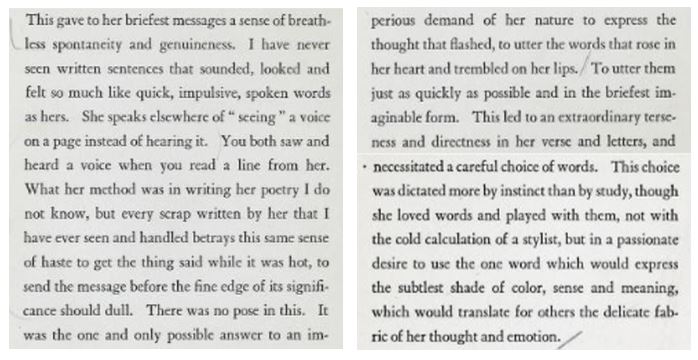

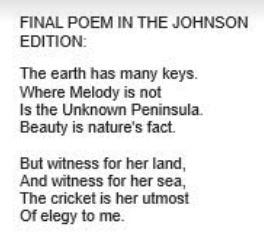

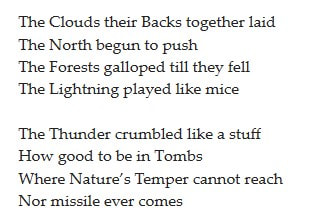

“Okay, I'm not gonna give up,” she tells herself. “Solitude never hurt anyone. Emily Dickinson lived alone, and she wrote some of the most beautiful poetry the world has ever known.” After a dramatic pause she adds, “Then went crazy as a loon.” LOL!

Well, there is no historical accuracy there – about going “crazy as a loon” – but the scene is funny!

You can hear her lines in the YouTube video HERE -– the part about Dickinson starts at 0:53.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed