Sooo…over time I’ll post info from the book and discuss various points, and today I’ll start with a compelling point made early in the book – in its introduction – and then turn to a poem by E. E. Cummings. Then tomorrow, I’ll have some discussion on another poem by Cummings – and soon thereafter I’ll return to Dickinson (and maybe even some lyrics by Dua Lipa?).

In “Positive as Sound,” Small wrote “...we may conclude that Dickinson had a strong, relatively unwavering sense of how she wanted her poems to sound and that she pursued that end deliberately.” Two pages later, she said, “that Dickinson’s rhymes are not the result of casual neglect.”

And it is that sense of “deliberateness” of poets – and painters, song-writers, sculptors, choreographers, photographers, etc. – and the fact that their work is not at all “the result of casual neglect” – that I’d like to examine this morning.

In poetry, every word, every syllable, every rhyme and every rhythm is pondered, planned, and purposeful – in short, everything is deliberate.

I definitely believe that is true – certainly close to 99% of the time. LOL.

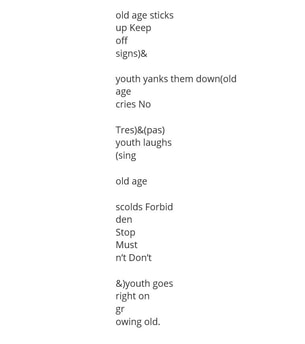

| Let’s take a look at E. E. Cummings’ “l(a" (shown at the right). In this poem, Cummings symbolizes loneliness as falling leaf – AND – he emphasized the concept of loneliness very deliberately in the way he dismantled, sliced, and rearranged the words. In the first line, he used a lowercase “L,” which looks like the number one, and it’s separated parenthetically (to emphasize isolation) from the letter “a,” a single article in English. In line 7, the word “one” appears, and in line 8, there is another lowercase “L” that looks like a number one. The structure of the poem – which represents a leaf falling to the ground – also depicts the structure of a number one – AND – the result at the bottom, “iness” (which I pronounce as “eye-ness,” i.e., the state of being “I”) – is the state of being one’s self. All of this arrangement was purposeful and deliberate. Everything about the poem symbolizes and emphasizes loneliness. |

What do you think? Cummings was VERY deliberate in his arrangement. He was extremely deliberate. There was no “casual neglect.”

So did Cummings purposely hew this poem to include the French singular articles? Was he, in fact, that deliberate?

Deliberate Intent -- Part 2

This idea grew from statements in Judy Jo Small’s book “Positive as Sound: Emily Dickinson’s Rhyme”: “...we may conclude that Dickinson had a strong, relatively unwavering sense of how she wanted her poems to sound and that she pursued that end deliberately”; and two pages later, she said, “that Dickinson’s rhymes are not the result of casual neglect.”

Before getting to a work by Dickinson, I posted a short – but very deliberately written – poem by E.. E. Cummings – and I did ask if a couple of details in the poem were, indeed, deliberate – or coincidental? (Refer to Part 1 of this post above.)

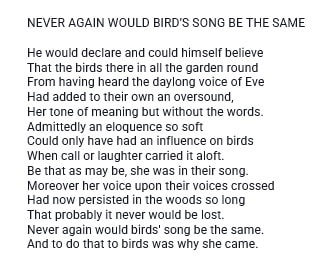

Before getting to a discussion of Dickinson’s (and others’) deliberateness, I’d like to offer one other poem by Cummings, “old age sticks.”

| This poem is obviously about generational differences/gap, and Cummings included some very creative details in emphasizing his point. For one, note that the language and images of the older generation are confined within parentheses – and the images of youth are outside those boundaries. Even the first line has a bit of a double meaning: not only does the older generation stick up signs of keep off, mustn’t and don’t – but older folks also often walk with “old age sticks” (i.e., canes). Of course, at the end of the poem, stark reality hits: the youth go right on growing old. When I teach this poem, I tell students that I believe there are two VERY important words related to the overall message of this poem. Hmm...what two words could they be? |

In the meantime – any guesses as to the two words I’m talking about?

Deliberate Intent -- Part 3

Yesterday, I posted a second E. E. Cummings' poem, “old age sticks,” and I mentioned that there were two words in the poem in particular that I felt were extremely important – and those two words actually come from the dissection of the poem’s final words “growing old”: Youth “goes right on growing old”; however, in the way Cummings split the words, youth also goes on “OWING old.”

Although the poem seems to focus on gaps and differences between generations, the ending subtly but masterfully recognizes that the newer, younger generation actually “owes” the previous generation for yanking down barriers, breaking glass ceilings, and stretching the boundaries they faced.

Of course, all of this discussion started when I quoted Judy Jo Small from her book “Positive as Sound: Emily Dickinson’s Rhyme”: “...we may conclude that Dickinson had a strong, relatively unwavering sense of how she wanted her poems to sound and that she pursued that end deliberately.”

| Later in her introduction, Small said this: “Her work as an innovator in the field of rhyme, furthermore, has permanently altered the ears of poets and readers.” She then quotes two lines from a poem by Frost (shown at the right): Never again would birds' song be the same. And to do that to birds was why she came. Over time, Dickinson’s work increasingly became viewed by scholars and the public as “innovative rather than flawed.” As a result, all of the generations of poets after Dickinson “owe” her (to use Cummings’ verb) for stretching the boundaries of what was thought to be formal poetry. More on this tomorrow. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed