Some recent posts focused on the poet's use of the dash -- so I have re-posted that info below.

1. From January 16, 2024:

| The Dickinson Museum’s Instagram account posted the pic shown at the right the other day (click the image to enlarge). It made me laugh – AND – it prompted me to run a Google-search on “Which poem by Emily Dickinson includes the most dashes?” While I did not find the answer to that particular question, I did find an interesting article to share. First, before I get to the article, just a refresher about dashes – and no, although Dickinson used many dashes in her poetry, the “Em Dash” is not named for her! LOL. I gotta say, though, this look into dashes can be a bit confusing. |

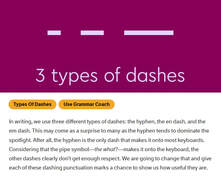

A site run by the University of Houston states, ”There are actually three different types of dashes: the em-dash, the en- dash, and the 3-em dash” – and they never mention the hyphen -- nor do they explain the "3-em dash."

From a site run by Georgia Tech, I found info on the hyphen, the en-dash, and the em-dash – but no mention of the double-hyphen or the 3-em dash.

| Dash it all! I'll look into all of this later. Sooo... Back in early January I made a post with a focus on dashes, and I included the poem “I tie my Hat – I crease my Shawl –” which has close to 50 dashes in it. I don’t know if that is the poem with the most dashes – so I’ll keep looking into that. For now,to access the article I mentioned earlier -- entitled "The Em Dash Is the King of All Punctuation — and Emily Dickinson Is His Queen" -- click HERE. FYI: I’ve turned to Grammar Girl on Threads for help on all of this! |

2. From January 17, 2024:

I’ve turned to Grammar Girl on Threads to see what she has to say about the subject, but for now, I tend to think there are three “dashes” – or really, one hyphen and two dashes, the en-dash and the em-dash.

When exploring all of this, I even stumbled upon “The Dickinson Dash Project” (isn’t it amazing how anything and everything can be found on the Interwebs).

To access "The Dickinson Dash Project," click HERE.

On a page titled “All About the Dash,” the author, a student at Tarleton State University, states,

“There are also two different 'types' of dashes thanks to modern day word processing systems. The 'em' dash is roughly the size of a capital M and is used in most situations that may require a dash, such as a pause or omission of letters. The second type of dash is the 'en' dash. The 'en' dash is about the size of a capital N and is used to separate chronological times or dates. In Emily's era, there was no distinction between the two, especially in handwriting, so it would be hard to differentiate between the two distinct ways to use the dash. In Emily's works, there are varying sizes of dashes, from long and bold dashes, to tiny, short, barely there dashes. Perhaps the way she wrote the dashes is of some significance as to the meaning behind them.”

Hmm…I’m not so sure about that line, “ In Emily's era, there was no distinction between the two” because typesetters working with a printing press surely would have known how to distinguish between a hyphen, an en-dash, and an em-dash; however, the caveat “especially in handwriting” is most certainly true.

If you explore the website, you’ll find that it was a college senior’s project, and while interesting, it is by no means an indepth look at Dickinson’s use of the dash nor did it delve all that deeply into her poems and letters. TBH, out of the nearly 1800 poems by Dickisnon, it explored fewer than a handful. Still, it’s fun to take a peek.

Also, it includes a list of sources which include some interesting titles of articles, like “The Grammar of Ornament: Emily Dickinson's Manuscripts and Their Meanings”; however, most are found on JSTOR – JSTOR is a site of “Journal Storage" and is a protected electronic archive of leading journals across many academic disciplines – and don’t include live links. If interested, you have to copy and paste the links into your browser – and then register at JSTOR (free registration allows you to peruse about 100 articles per month).

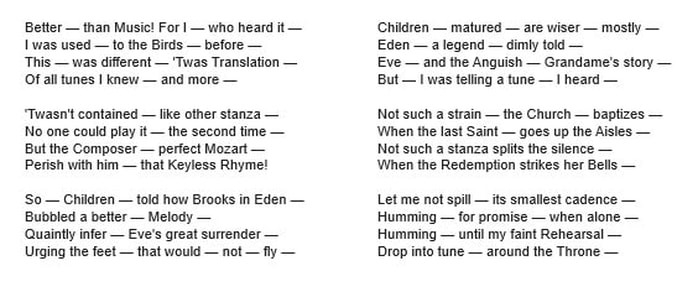

Anyway, back to Dickinson and her use of the dash. I thumbed through my Johnson edition of Dickinson’s poems and one with 50-plus dashes caught my eye, “Better – than Music! For I – who heard it –.”

Is that the one with the most dashes? I have no idea – but take a peek at that one just for fun!

3. From January 18, 2024:

At one point I stated that I would turn to Grammar Girl on Threads for help with this, & I added that "I tend to think there are three ‘dashes’ – or really, one hyphen & two dashes, the en-dash & the em-dash.”

Lo and behold, I received a reply from @GrammrGirl, and she sent an article that validated my thought. In the section on “Hyphens and dashes” she provided “key rules” for using hyphens, en dashes, and em dashes – and there is no mention of a double-hyphen, or a 3-em dash.

OOPS! I’d been writing them as “en-dash” and “em-dash” – but they’re just “en dash” and “em dash.”

To see what @GrammarGirl has to say -- i.e., the complete article -- click HERE.

Of the rules she lists in the article, I would say those related to Dickinson’s uses for the dash are “to create a strong sense of separation or emphasis,” “where commas or parentheses aren’t enough in a sentence” and to “add emphasis.”

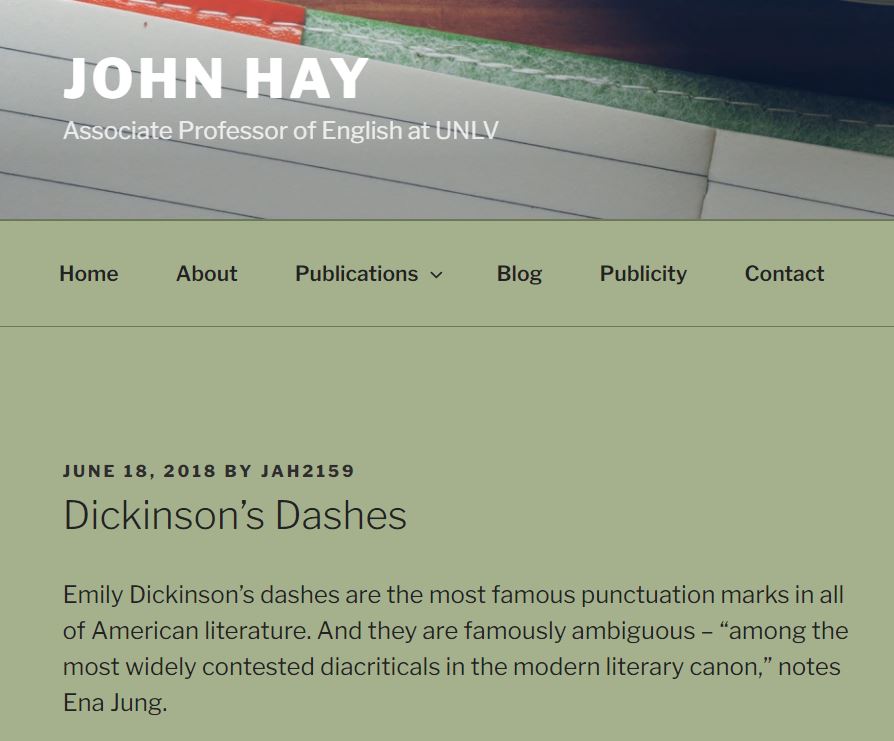

| A page on the Dickinson Museum’s site also states this: “While Dickinson’s dashes often stand in for more varied punctuation at other times they serve as bridges between sections of the poem—bridges that are not otherwise readily apparent. Dickinson may also have intended for the dashes to indicate pauses when reading the poem aloud.” To access that site, click HERE. There are as many theories and articles on the Interwebs as to why Dickinson added more than a dash of dashes to her poetry, so here’s one more that raises the question as to whether or not Dickinson’s dashes are even conventional dashes. The blogger states that “they are famously ambiguous,” and quotes Ena Jung as saying they are “among the most widely contested diacriticals in the modern literary canon.” To access this blog, click HERE. |

4. From January 19, 2024:

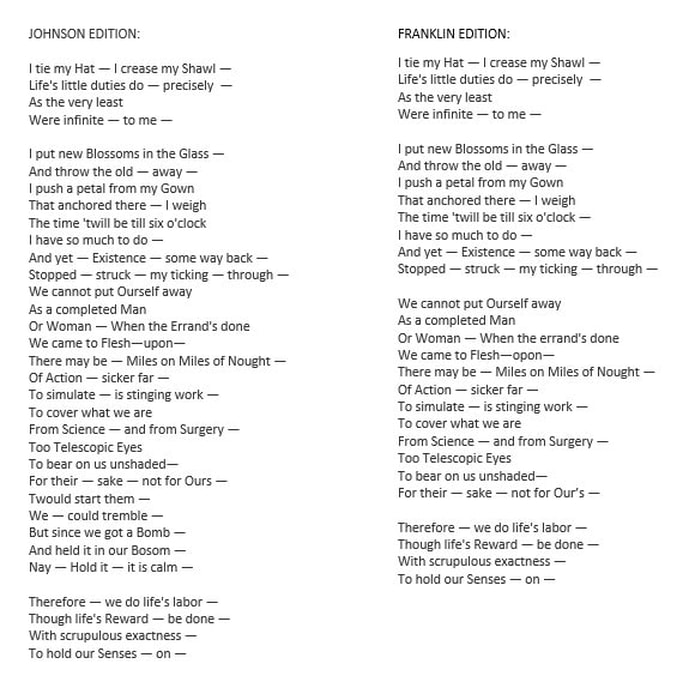

One site for which I posted a link yesterday, the blogger made the following observation about the Johnson & Franklin editions of her “complete poems”:

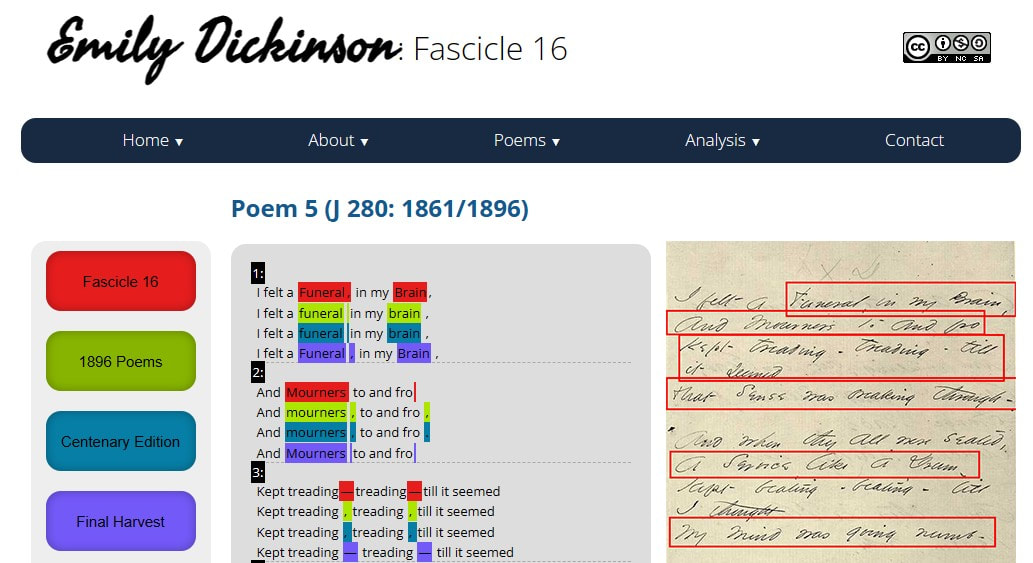

“Thomas Johnson’s monumental 1955 edition of The Poems of Emily Dickinson went with the medium-length en-dash (my own personal preference). Ralph W. Franklin’s authoritative 1998 edition of The Poems of Emily Dickinson shrunk them further by using mere hyphens. (And now the online Emily Dickinson Archive makes it easy to view the poet’s original manuscripts, potentially eliminating the need for standard typography.)”

He then added this:

“Such a shortening is not without its effects. ‘Has our experience of Dickinson’s writing altered, if subliminally, with these changes?’ asks Loeffelholz. Are we reading a different Dickinson?"

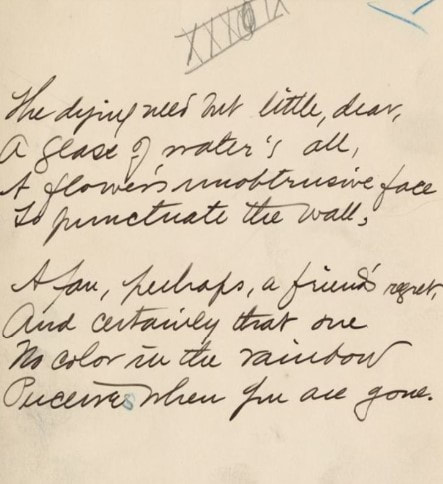

As a result of these comments, I spent more than a little time yesterday exploring MANY of Dickinson’s poems in her own handwriting – and I have to admit – I was completely surprised to see how consistent she was in most cases with the size of her dashes. I was expecting to see a greater variety in dash lengths – but no; they were rather uniform – much closer to the “mere hyphens” as used by Franklin – and this realization underscored the fact that when it comes to Dickinson’s dashes, one must reflect upon their placement and purpose – a point made in a comment by CoSo’s @Bliss:

“Linguistics also needs to be considered when analyzing and parsing Dickinson's poetry. Are the dashes a stand-in for the pregnant pause. Dickinson used language to evoke many visual scenes in her poetry. Those dashes or linguistic pauses can represent a New Englander's thoughtful reflection during a conversation, in which Dickinson peers into her imaginary reader's eyes, pausing to search for the correct word or phrase or to create emphasis on what follows.”

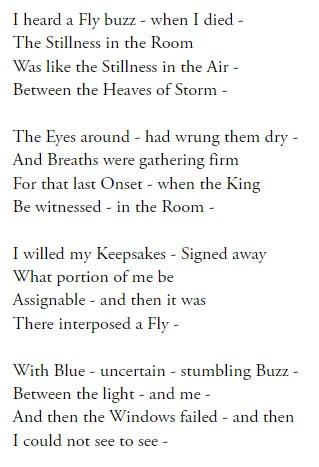

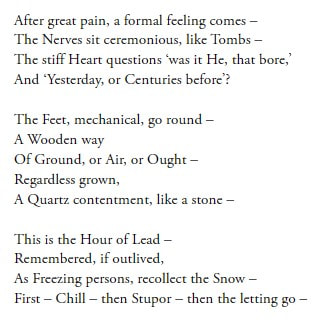

I will say that two of my favorite poems – especially related to Dickinson’s placements of her dashes – are “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –” and “After great pain, a formal feeling comes –” –particularly the poet’s use of dashes in the final stanza of each poem – and in the case of “After great pain,” even the use of dashes in the final line: First – Chill – then Stupor – then the letting go –

Fin –

RSS Feed

RSS Feed