Sunday, April 28:

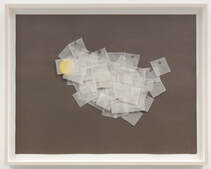

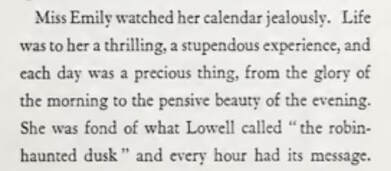

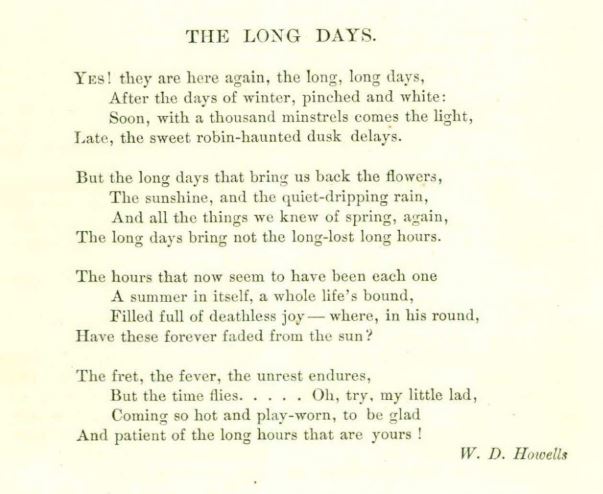

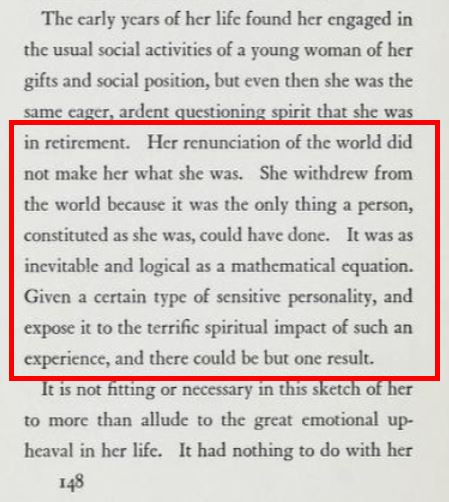

| On the day after the final installment of that week, I posted Dickinson’s poem “The clouds their backs together laid,” and I included an artwork by contemporary artist Spencer Finch – the post is HERE. Pictured at the right: “Cloud Over Sun Study, 2010" by Spencer Finch At the time of that post, I mentioned that “one of these days” I would devote a week to Dickinson’s poems about clouds. Well, that day (and week) is here: A week of cloud poems! |

| I've looked at clouds from both sides now From up and down, and still somehow It's cloud illusions, I recall I really don't know clouds at all However, when I ran the search and found the list of the 18 songs, other lists also popped up – and I saw lists with 20 songs, 21 songs, 22, 30 44, 50-plus, and even 105 songs. LOL. There are a lot of songs about (and with) clouds. I’ll stick with just 18 -- and that list is HERE. |

More on clouds and cloud poetry tomorrow!

Monday, April 29:

The word “cloud” appears in 27 different poems, and today I’m going to feature “A curious cloud surprised the sky”; however, before I get to that “curious cloud,” let me start with a question similar to that enigmatic opening line of Ayn Rand’s “Atlas Shrugged”:

Who was Ebenezer Snell?

Ebenezer Snell was the first student in the first class (1822) to graduate from Amherst College, and he was also the first college graduate to teach at Amherst Academy and the first alumnus to return to the college as a professor. He taught mathematics and natural philosophy.

For many, many years – decades, in fact – Snell would rise to record daily measurements and scientific observations about the day in “The Meteorological Journal Kept at Amherst College.” His daily calculations would include barometric pressure, temperature, winds, “fall of water,” “cloudiness,” and more. Snell’s “cloudiness” scale ran from 1 to 10, with 10 being a cloud covered day.

Every year Snell would add new columns and categories to his tabulations—wet bulb measurements, dry bulb measurements, mean temperature. “Pure Air” was a frequent entry in his logs.

You can read a bit about his weather-related work HERE.

So why this info about Ebenezer Snell and his daily observations?

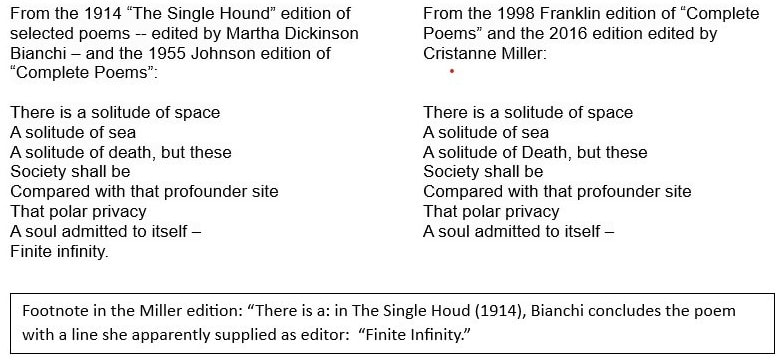

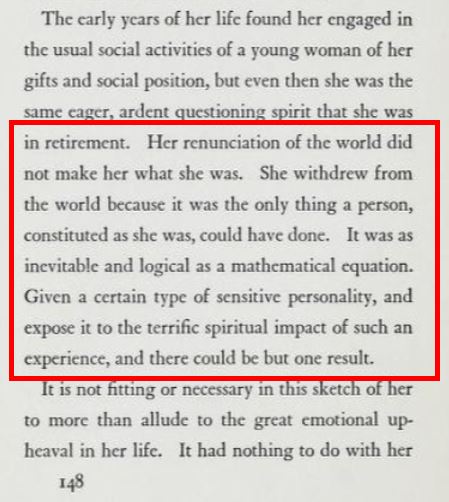

| Well, take a look at Dickinson’s poem, “A curious cloud surprised the sky.” Wow, what a cloud Dickinson saw in the sky that day – and I wonder what day, exactly, she penned this poem. It would be interesting to know the date, and then to check Snell’s notes to see what could have been going on that day to produce such a magnificent cloud. The Johnson edition of “Complete Poems” lists no year for this poem (i.e., date unknown). The Franklin edition lists “1863,” and the Miller edition shows this poem in Fascicle 24 – from 1863. Hmm…1863. What could have been going on in 1863 to produce a cloud of blue and gray? |

What do you think?

Bonus bit:

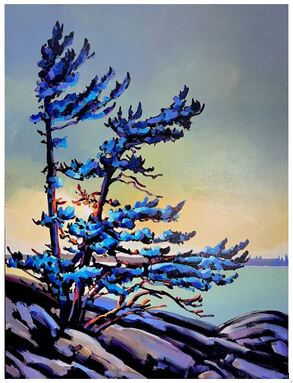

| Looky what I found: the painting on the right by artist Jerzy Werbel is entitled "A Slash of Blue." I suspect that Werbel is familiar with Dickinson and her poem "A slash of Blue -- A sweep of Gray," below. It, too, is a poem about the sky -- with images of blue and gray like "A curious cloud surprised the sky" -- although it doesn't include the word "cloud." A slash of Blue -- A sweep of Gray -- Some scarlet patches on the way, Compose an Evening Sky -- A little purple -- slipped between -- Some Ruby Trowsers hurried on -- A Wave of Gold -- A Bank of Day -- This just makes out the Morning Sky. |

Tuesday, April 30:

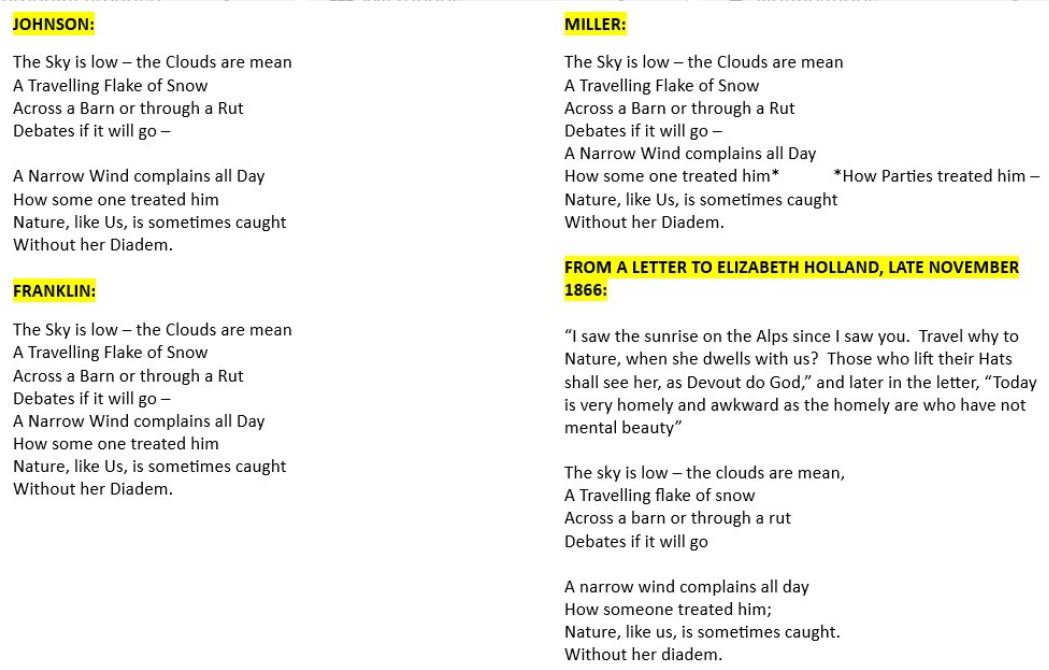

This poem was not included by Dickinson in any of her fascicles; instead, it was a stand-alone poem included in a letter to her friend Elizabeth Holland.

Below are copies of the poem as they appear in the various editions of “Complete Poems” – and I’ve also included a few lines from the letter. The complete letter is HERE.

| I love the idea presented in this poem – an angry sky presaging inclement weather (LOL – especially in the days before Doppler radar!), and I particularly liked the image of the “narrow wind” complaining all day! Hmm…maybe at some time in the future I’ll present a week-long special of Dickinson poems dedicated to the wind! Oh, I also found today’s poem as a feature on a short (< 6 minutes) podcast called “The Daily Poem." Click HERE, or click the pic at the right. |

Wednesday, May 1:

| Very quickly, Dickinson sets the scene of a cloudy and almost starless winter night. Don’t you love that image of the timid star blowing itself out as “often as a Cloud it met”? Of course, the wind has swept the leaves away, and November is “clambered up” in the Eaves. By the fourth stanza you realize a housewife is snuggled up by the fireside, most likely alone – and is she conversing softly with the empty “sofa opposite” Or could the “sofa” be a reference to an inattentive and unobservant husband (a couch potato, LOL) who is totally unaware of the tender moment when she whispers “how pleasanter” is the sleet than a May without him? This poem was written during the Civil War in 1863 – so could she be referencing a housewife whose husband is off fighting in the war? Could there be other interpretations of this poem &/or the final stanzas? |

Thursday, May 2:

| This poem is such a casual and coquettish conversation – albeit one side of the conversation – that I can just imagine Dickinson on the phone or texting this with a lover. Line 7 could very well be a Biblical reference – though I am NOT any sort of Bible scholar (or Bible reader, for that matter) – but could it also reference Melville? Hmm...possibly, since “Moby Dick” was published in 1851 and this poem was written in 1863. Anyway, whichever Ishmael is referenced, a length of time has passed since she & her lover have been together (a common theme in Dickinson’s poetry), so she must turn to the moon to see his face. |

In one blog I came across, the writer made this comment: “Judith Farr makes a good case (The Passion of Emily Dickinson) for Ishmael being Samuel Bowles who was, if not Dickinson’s Beloved, at least one her most treasured friends. The poem’s playful tone would be appropriate, and Bowles happened to be out and about in the world during the time this poem was probably written.”

Hmm. Maybe so. I’ve not read “The Passion of Emily Dickinson.” Just FYI, here’s a bit from a blurb about the book: “In a profound new analysis of Dickinson's life and work, Judith Farr explores the desire, suffering, exultation, spiritual rapture, and intense dedication to art that characterize Dickinson's poems, and deciphers their many complex and witty references to texts and paintings of the day.”

| However, I’ll just throw this out there: In another poem, “The moon was but a chin of gold,” the commonly accepted “man in the moon” isn’t a man at all. In Dickinson’s poem, the moon is a woman. “The Moon was but a Chin of Gold / A Night or two ago – /And now SHE turns HER perfect Face / Upon the World below –” It makes one wonder just whose face was Dickinson seeing in the moon the night she wrote “You know that Portrait in the Moon.” |

Friday, May 3:

| f course, the poem is about the passage of time – leading up to death (for “Conclusion is the course of All”), and the first two stanzas move quickly from Summer to Autumn. Of the two stanzas, I love the images of the second, the “millinery of the cloud” and the “deeper color in the shawl / That wraps the everlasting hill.” I like the way the first stanza begins, with Summer having “the look /Peruse of enchanting Book” – but lines 3 and 4 are a bit cryptic. What do you make of those lines? I’ve always heard that “backward leaves” are a sign of an imminent storm – and I suspect that Dickinson knew this – so the pages of Summer’s “enchanting Book” tell of a coming tempest? However, the beauty of the second stanza and the meditative turn in the third stanza don’t seem necessarily to lead to any turbulence. Melancholy, yes. A tempest? Not so much. |

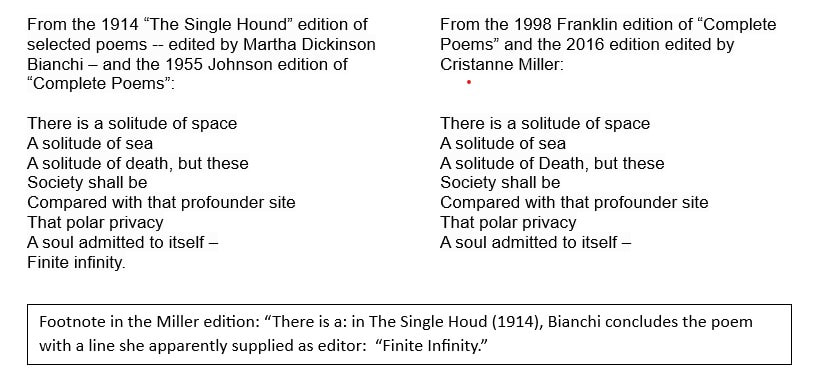

The final stanza concludes the poem with a reality of life: “Conclusion is the course of All” (pun intended) – but those final three lines are quite enigmatic: “Almost to be perennial’ (“At most to be perennial” is used in the 1955 edition of “Complete Poems”); okay, Emily, I’m with you; “And then elude stability” – um, maybe if one were “perennial,” one would baffle if not circumvent the “stability” of the existing conditions of life – and (to the final line) realize immortality?

Thoughts?

Saturday, May 4:

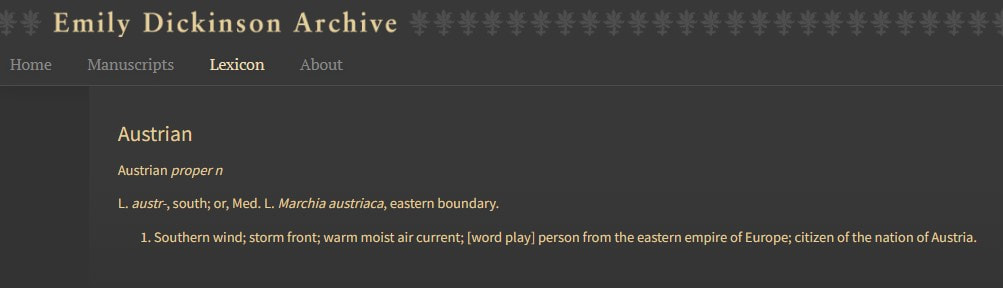

| “The wind drew off” is a straight-forward poem about storm-like conditions, and it includes some great images: the wind drew off “like hungry dogs”; the “volcanic” clouds; the trees with their “mangled limbs.” Dickinson must have experienced quite a storm! I included this poem, though, because of that very odd final warning: “When Nature falls upon herself / Beware an Austrian.” That “Beware an Austrian” threw me. What is she talking about? Click the image at the right to enlarge. |

I ran a few searches about an “Austrian” as related to the weather, and I found current weather forecasts for Austria along with various references to Nazi movements in World War II. However, I didn’t find any weather phenomenon referred to as an “Austrian.”

I’ve heard of Alberta clippers – but not Austrians! LOL. Does this ring a bell with anyone?

PS: I checked Cristanne Miller's “Notes” associated with the poem, and I found this:

“Austria and Italy were sometimes associated with treachery by predominantly Protestant countries, because of their Catholicism. ED may also associate Austria with the tyrannical Albrecht Gessler, who, according to legend, forced William Tell to shoot an apple off his own son’s head.”

Miller concludes the note with “see “Tell as a Marksman – were forgotten.” Okay, we’ll take a look at that tomorrow.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed