| It all started when I posted William Carlos Williams’ poem about the red wheelbarrow, plus I posted E. E. Cummings’ poem “l(a” followed by Cummings’ poem “old age sticks. With that particular poem I discussed the idea of artists pushing boundaries, setting the stage for change, and then I posted pictures of contemporary artworks currently being shown at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City. You can view them all HERE. My wife and I were talking about artists who pushed boundaries – from writers, poets, visual artists and more – and in the conversation I mentioned John Cage from the field of music. Have you ever heard his work entitled 4’33”? The title refers to the length of the piece – it is four minutes and thirty-three seconds long. If you’ve never heard it, take a listen now – and then let me know your thoughts. |

|

With my daily posts lately I’ve been discussing what makes a poem a poem and what defines art. To listen to the piece, click the image below -- or click HERE.

0 Comments

I’ve been writing about how, as a song-writer who sets Dickinson’s poems to music, I deal with the fact that so many of the poems are short.

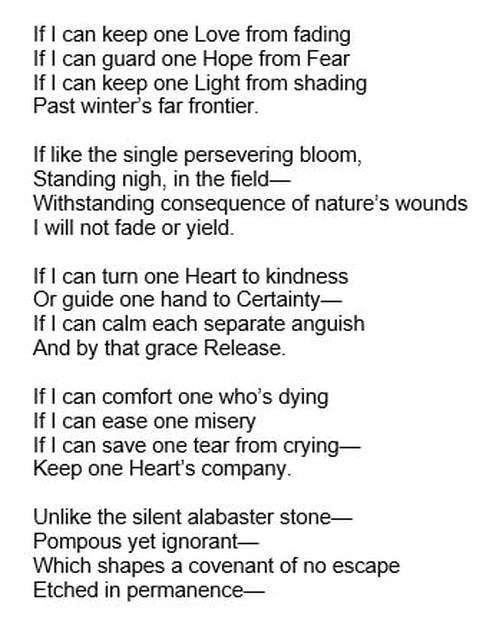

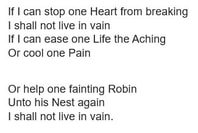

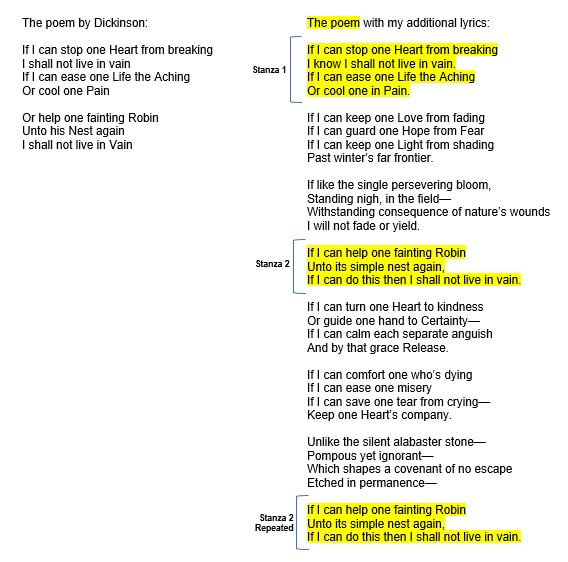

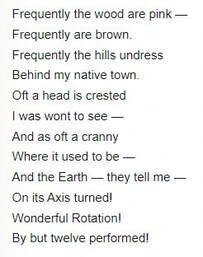

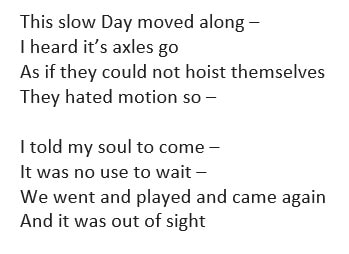

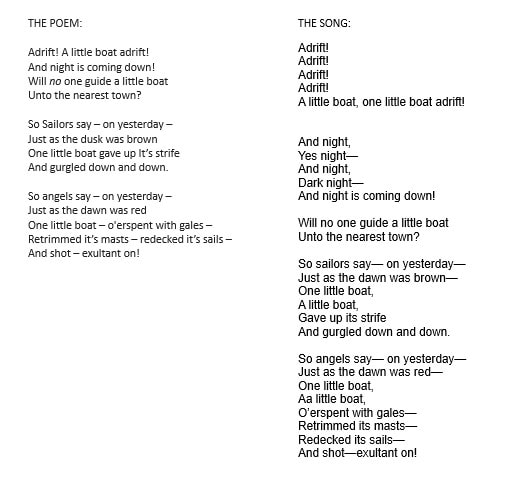

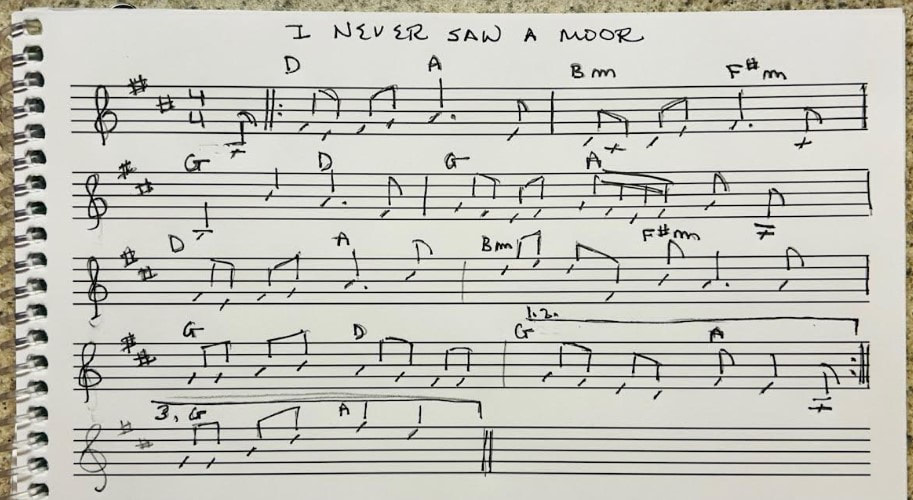

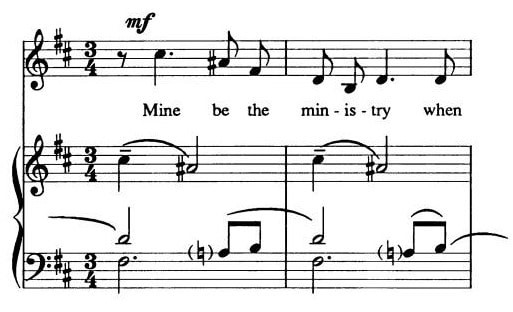

1. I’ve repeated a short poem several times (and I’ve even embedded some in well-known songs in the public domain – like Pachelbel’s Canon). 2. I’ve written short songs. LOL – short poems – short songs! 3. I’ve combined poems with similar themes/moods. 4. I’ve repeated words and lines to lengthen a poem a bit. 5. I’ve even written my own lyrics to add to a poem. There are other methods too: 6 .One reader said in comment yesterday, “another strategy, common in rock songs, is to simply add a minute or so of instrumental intro. Then you don't need so many words in a song!” – and I’ve done that with introductions and musical interludes in the middle of songs. 7. I’ve also taken lines or stanzas to create a “chorus” that repeats throughout the song (typically, songs are made up of “verses” followed by a “chorus,” often the part that contains the most memorable or catchy part of the song). In the song I wrote pictured below, I combined two poems – AND – I borrowed some lines to create a chorus that repeats several times. Before I continue with a post on setting Dickinson’s poetry to music, let me say that Punxsutawney Phil did not see his shadow this past Friday morning at Gobbler's Knob in Punxsutawney, PA. That means, according to the legend, we're in for an early spring – and that’s a good thing – cuz check out these lines Dickinson wrote to her cousins in 1871: “The will is always near, dear, though the feet vary. The terror of the winter has made a little creature of me, who thought myself so bold.” An early spring will cure that! Now, back to my discussion on issues songwriters encounter when trying to set Dickinson’s poems to music – because so many of them are short (the poems, that is, not the songwriters). #badumpbump One post suggested a songwriter could repeat the melody – and poem (i.e., the lyrics) – several times. Another post: Just write a short song. A third post about working with Dickinson’s shorter poems said to combine them and use two or three poems together. In that post I also discussed a fourth way to add a bit of “time” to a poem for a longer song – by repeating words, phrases or lines from the poem. A fifth way to handle Dickinson’s shorter works is… Well, before I get to the fifth way, take a look at the lines below – and then I’ll explain the fifth way tomorrow. Fifth Dimension Continued...I’ve been discussing issues that songwriters face when setting Dickinson’s poetry to music – especially her shorter poems – and yesterday I alluded to a “fifth way” to handle the problem. I also posted a set of lyrics to check out (aee above). Sooo…the “fifth way” to work with the poet’s shorter poems is to add additional lyrics! LOL – but this can be somewhat risky – and I did it with one poem/song. Here’s the story, and it involves one of the first songs I wrote based on a poem by Dickinson, “If I can stop one Heart from breaking.”

Sooo…I set about to write additional lyrics – and I have to say I failed miserably! Oh, I did write some lyrics, but when I played the song for a friend – who was not necessarily a fan of Dickinson – she recognized immediately that something was up: After the first few authentic lines from the poem, she said, “Well Dickinson didn’t write that,” about the lines that followed. At the time, she didn’t know that I was the one who had written the counterfeit lines, but she did realize quickly enough that the lines were not Dickinsonian – so I ditched those lines and went back to the drawing board! On my second attempt, I came up with the lines I posted yesterday – the very lines in the pic below (compared to the poem). LOL – I don’t necessarily recommend this method of augmenting a poem for a song – that is, writing additional lines a la Dickinson – but I did it the one time and it turned out okay. It wasn’t easy – for sure – but what do you think?

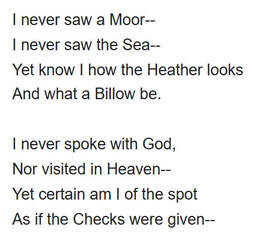

Do the lines sound Dickinson-esque (or at least Dickinson-ish)? I’ve been discussing issues songwriters encounter when trying to set Dickinson poems to music, and the first and foremost problem is the length of many of her poems – that is, some are so short you could end up with a 30-second song. LOL. One way to handle this “problem” is to repeat the poem several times – and/or to embed it into another song – as I did with my melody for “I never saw a moor” and Pachelbel’s Canon (for more on this, click HERE).

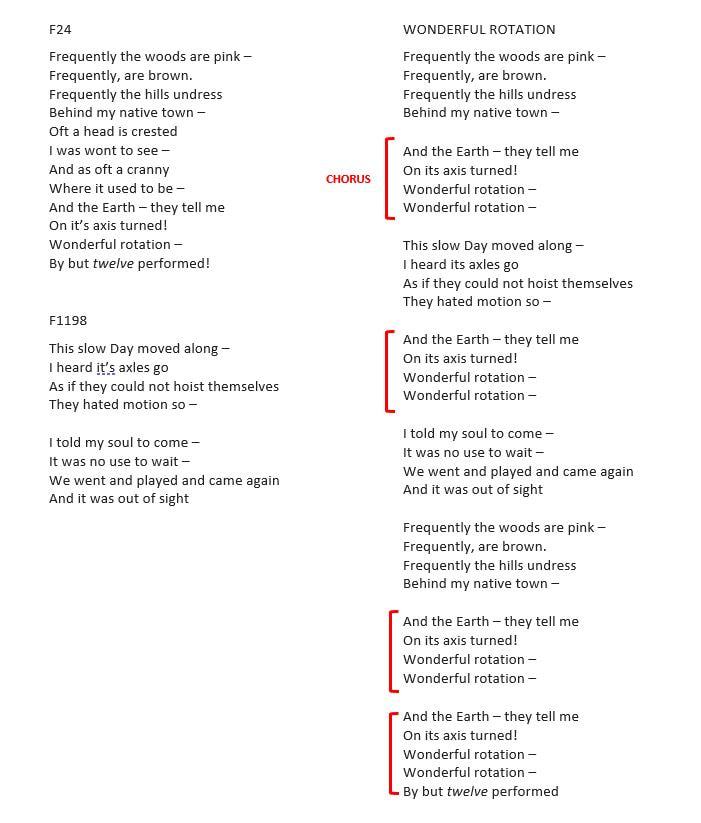

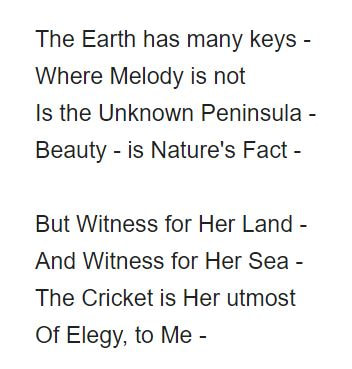

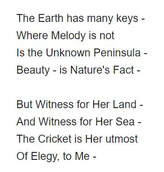

This past December a friend of mine helped me with a birthday celebration event for Emily Dickinson’s 193rd birthday. She sang my original songs based on ED’s poetry, and I played the piano. I came across the line “The Earth has many keys,” so we landed on that as the name for our event – and I decided to compose a song based on that poem. Info on our event is HERE. My first inclination – based on the first four lines of the poem – was to write something upbeat. After all, lines 1 and 4 state, “The Earth has many keys,” (sounds happy to me) and “Beauty is nature’s fact,” and lines 2 and 3 mention – albeit a bit awkwardly – “Where melody is not / Is the unknown peninsula.” But then I read the final four lines, and I changed my mind from writing some sort of rosy, hopeful song to composing – **drum roll please** – an elegy! Afterall, there it was in line 8, the word “Elegy.” I read the poem with a very modern perspective with a focus on climate change: As beautiful as our planet is, we are not doing enough to protect it; witness what is going on with our land and seas (lines 5 and 6) – and the sound of crickets – signifying our silent response to all the warning signs – is the Earth’s “utmost of Elegy, to me.” I ended up with a slow and somber melody, and the song lasts all of about a minute and twenty-seconds. Oh, I also challenged myself to change keys when possible (since the first line is “The Earth has many keys”) – so not an easy task with such a short composition. Short & Sweet continued:Recent posts have dealt with issues songwriters encounter when trying to set Dickinson poems to music – because so many of them are short! One way to handle this issue is to repeat the poem several times – and/or to embed it into another song – as I did with my melody for “I never saw a moor” and Pachelbel’s Canon. Another way to handle this is just to write short songs! The elegy I wrote for “The Earth has many keys” clocks in at just under a minute and a half. A third way to deal with Dickinson’s shorter poems: combine them! That’s what I did with a song I wrote entitled “Wonderful Rotation.” The song focuses on two different poems by Dickinson: “Frequenlty the woods are pink” and “This slow day moved along.” The title for my song comes from the penultimate line of “Frequently the woods are pink.” In the song, I juxtaposed these two poems because one conveys the rapid passage of time, and the other emphasizes the opposite – until, in its second stanza, it ends with a brilliant twist of irony! A fourth way to add a bit of “time” to a poem for a longer song is to repeat words, phrases or lines. Dickinson’s poem “Adrift! A little boat adrift!” is relatively short, and I added a bit to it by repeating the word “adrift” and by adding other repeating lines. I have one more -- albeit unusual -- way of handling Dickinson's shorter poems when setting them to music. I'll post that soon!

Rodgers and Hammerstein posed the question, “How do you solve a problem like Maria?” Similarly, how do you solve a problem like Emily Dickinson – if and when you’re setting her poetry to music? Recently I’ve been writing about Michael Cherlin’s article “Thoughts on Poetry and Music, on Rhythms in Emily Dickinson’s ‘The World Feels Dusty’ and Aaron Copland’s Setting of It.” For the most part, the article focuses on how Copland’s use of rhythm (as stated in the title of the article, i.e. “rhythms” vs “melody”) was limited by restrictions brought on by the punctuation modifications made by the publishers of the 1929 version of the poem – and yesterday I concentrated on Cherlin’s look at the final stanza of the poem (“the problem child,” in Cherlin’s words) and his discussion on Copland’s use of a ”durational palindrome.” I concluded my comments with “Dearest reader, have I confused you completely with all of this? And what does it all mean? Well, for one thing – setting Dickinson to music is not an easy task!” So let’s talk about the issues – what are the problems with setting Dickinson’s poems to music? First and foremost, there’s the problem of the length of the poems – so many of them are short. As a result, if you set a short poem to music, you end up with a song that lasts, say, thirty seconds. LOL. So what to do, what to do? Well, on the one hand, one could ignore all of the shorter poems; on the other hand, there are strategies one could employ to allow for a wider-range of possible poems to consider.

So here’s another non-Dickinson-related issue composers face: thou shalt not plagiarize. And the truth of the matter is, any individual has encountered thousands upon thousands of songs – and consciously or sub-consciously, those songs are embedded within their experiences and spirits. As I played my newly composed opus based on “I never saw a moor,” I kept thinking to myself, “Hmm…where have I heard this before?” It turns out – I not only wrote a beautiful song based on “I never saw a moor,” but I also re-wrote a classic. How did I solve my issue? I embedded my new melody within the well-known and time-honored tune (which, BTW, is in the public domain). Take a look at the pic for my melody – and chords – and see if you recognize what “classic” I re-wrote! LOL. Less is Moor, continued:Yesterday I discussed one problem with setting Dickinson’s poetry to music: the length of many of her poems – or should I say “the brevity.” Set a Dickinson poem to music and you might just end up with a very short song. Also yesterday I posted a melody I wrote for “I never saw a moor” – along with the chord progression I came up with – which I quickly came to realize was nothing more than a re-write of Pachelbel’s Canon! LOL! BUT – I used my unintended plagiarism to my advantage, because I embedded my musical version of “I never saw a more” into the well-known piece, repeated it three times – and voila – I ended up with a pretty decent song. The pattern is this: 4 measures of Pachelbel (with its complete chord progression), my version of “I never saw a moor,” 4 more measures of Pachelbel, my melody again, 4 more measures of Pachelbel, the third and final version of my composition, and then 8 concluding measures of Pachelbel.

So back to the matter of setting “The Earth has many keys” to music: One early matter a song-writer has to deal with – besides the length of the poem – is “what type of song do I write? Something upbeat and positive? Something slow and sad? Something mournful or uplifting? Something inspirational or lighthearthed? Take another look at “The Earth has many keys.” What kind of song would you write? What mood would it reflect? Think about it – and to see the decision I made about this poem/song, click HERE. In recent posts I’ve been writing about Michael Cherin’s article “Thoughts on Poetry and Music, on Rhythms in Emily Dickinson’s ‘The World Feels Dusty’ and Aaron Copland’s Setting of It.” For the most part, he discusses Copland’s use of rhythm (as stated in the title of the article, i.e. “rhythms” vs “melody”), and how the composer was limited in his work (in creating the rhythms) by restrictions brought on by the punctuation modifications made by the publishers of the 1929 version of the poem. To access the complete article, click HERE. One interesting section of the essay I’d like to highlight, involves a concept I’ve never heard of before, but before I get there let me explain a few musical principles about rhythm. First, think of a “beat” of a song. A march might be 1 - 2 , 1 - 2 , 1 - 2 , etc. A waltz is 1 - 2 - 3 , 1 - 2 - 3 , 1 - 2 - 3 , etc. A mainstream song might have 4 beats: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 , 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 , 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 , etc. Sooo…the “1” in each case is called the “downbeat” – the starting beat of each “measure” of music (and I’ve separated the “measures” with commas). Therefore, if one were to set Dickinson’s poem “Shame is the shawl of Pink” to music, it is highly likely the composer would start the vocal line by putting the word “Shame” on the downbeat. On the other hand, if writing a song for “The Sun just touched the morning,” it very likely the word “sun” would be on the downbeat, and the word “the” would be an unstressed syllable before the downbeat (that’s called up an “upbeat,” an unaccented beat preceding an accented beat). Back to Copland’s rhythms – and Cherlin’s discussion of them: Take a look at the starting words to the first three lines of the poem “The World feels dusty." NOTE: In the discussion forthcoming, I will use “u” for an unstressed syllable, and “/” for a stressed one. Here’s what Cherlin said: “The pattern of a single upbeat, ‘The world,’ to double upbeat, ‘When we stop,’ is extended one step further for opening line three, ‘We want the dew then’ ( u u u / u ). And the pattern continues further yet.” NOTE: Cherlin’s discussion gets quite complicated at this point – if you’re a musician interested in the particulars, navigate to page 12 on the PDF article linked above. Back to Cherlin’s comments on stressed/unstressed notes and the concept I’d never heard of before (mentioned at the start of this post – and please note, I added the ALL CAPS in the quoted section below): “The final stanza is the problem child. Compared to the other stanzas it remains awkward, even in the authentic version, and more so in the 1929. ‘Mine be the ministry’ has a conflict between stressed/weak syllables and long/short speech durations. The former suggests a scansion of / u u , / u u , while speech rhythms in terms of duration suggest / u u , u u / . Copland solves the problem neatly by using a DURATIONAL PALINDROME in conjunction with a metric placement that correcsponds with syllabic stress. The delayed entrance of ‘mine’ participates in a short canon between voice and piano.” Say what? A “durational palindrome”? LOL. I had to read that more than a couple of times until I figured it out that the “durational palindrome” was this: / u u , u u / BUT – I have to say that if I understand all of this correctly, I disagree with Cherlin when he says “The former suggests a scansion of / u u , / u u , while speech rhythms in terms of duration suggest / u u , u u / .” I think that “speech rhythms” necessitate / u u , / u u – and I’ve listened to the Copland rhythm several times now and…

Dearest reader, have I confused you completely with all of this? And what does it all mean? Well, for one thing – setting Dickinson to music is not an easy task! LOL. More on that later!

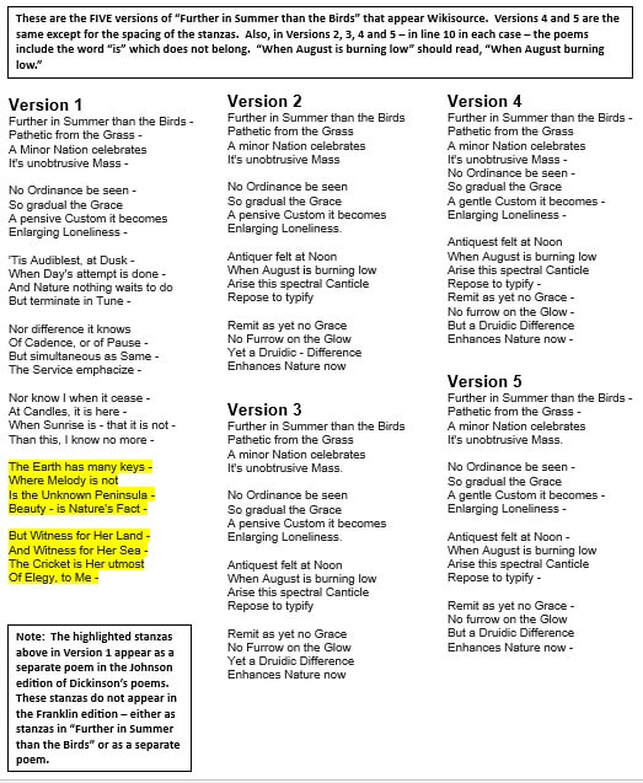

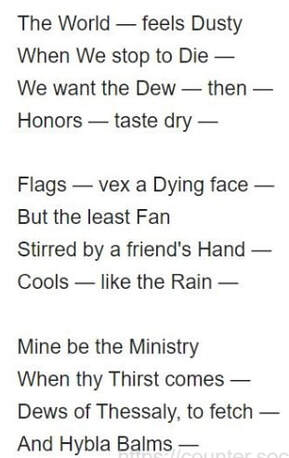

NOTE: TO ACCESS EARLIER POSTS ON AARON COPLAND'S SONG-CYCLE BASED ON DICKINSON'S POEMS, CLICK THE BUTTONS BELOW: Many of my recent posts have focused on Aaron Copland’s 1950 12-movement song-cycle, “The Poems of Emily Dickinson for Vocals and Piano.” Specifically, I explored the versions of the poems Copland selected – for at the time of his work’s premiere, Thomas Johnson’s seminal publication “The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson” had not yet hit the market. While looking into this, I stumbled upon a very interesting article by Michael Cherlin that specifically focused on Copland’s 4th song, “The World Feels Dusty.” The article is HERE. As one who writes songs based on the poetry of Dickinson (and other poets too), I found the article fascinating I were – and if I were to “boil it down,” the overall gist of the essay is reflected in this statement from page 64: “Within the first stanza’s vocal part, Copland has projected a hierarchy of articulations that clearly represent the 1929 version of the text, and clearly obfuscate alternative readings suggested by the authentic version.” In other words, Copland’s mastery and methods as a composer were influenced by – if not limited and/or determined by – the 1929 modifications and punctuation of the poem as made by the early publishers. One point Cherlin makes more than once in his essay is that he is not judging Copland’s work because of this, Instead he focused on how the composer approached the work based on the version of the poem that was available from the 1929 publication. The pic below on the left is the version from 1929, published many times, including in the Atlantic Monthly (Volume 143), before the more authoritative version came out with the more characteristic punctuation, below on the right. I love the analogies Cherlin makes in his opening paragraph of the songwriter approaching the poem – as an intruder, a gardener, or an interior designer – and he returns to a similar connection in his conclusion, the composer as some sort of aggressor: “Assailed at all sides, the poem is placed at the mercy of the composer’s whims.” “Still,” he adds as he softens his anaolgy , “composers set poems that they love (to music), and love brings tender care.” He then acknowledges that “good poems do not need the musical settings that composers bring. Likewise, music…does just fine without text.” “When though, the match is well-made,” he concludes, “…the wedding of sound and sense creates new meaning for both. In creating new meaning we stand at the beginning.” A Little More on the Topic from My CounterSocial Post on 1/28/24:Yesterday I posted information about an article on “Thoughts on Poetry and Music, on Rhythms in Emily Dickinson’s ‘The World Feels Dusty,” the fourth movement in Aaron Copland’s 12-movement song-cycle based on selected poems by Dickinson.

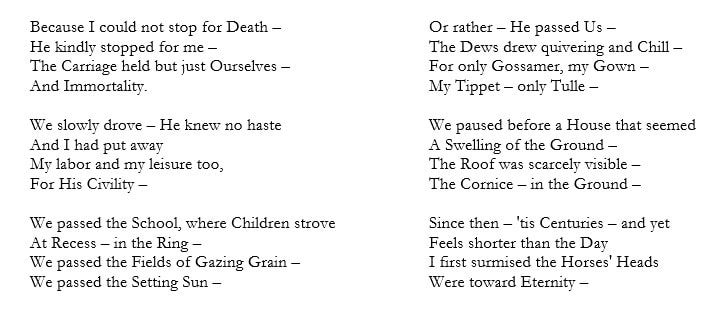

The gist of the article is that Copland’s craft as a composer was influenced by – if not limited and/or determined by – the 1929 modifications and punctuation of the poem as made by the early publishers. Cherlin makes the point that a composer writing a song based on a poem will – obviously – focus on the rhythm and flow of the lines – but will also be driven by how he perceives the stress of syllables. Consider the sentence, “I didn’t kick your dog.” One can interpret that line in one of five distinct ways: I didn’t kick your dog. I DIDN’T kick your dog. I didn’t KICK your dog. I didn’t kick YOUR dog. I didn’t kick your DOG. Back to the article on “The World Feels Dusty,” Cherlin said, “The different readings are different because of rhythm and accent, with accent properly understood as a subspecies of rhythm,” and “Most well-made poems play on multiple layerings of rhythm.” Of course, based on that last statement, Copland was at a disadvantage because he was “fenced in” by the limitations of the punctuation set by the publishers of the 1929 version of “The World Feels Dusty.” The actual poem includes – as Cherlin states – “the equivocal Dickinsonian dash, found in every line save two.” As a result, the dash can “suggest a pause” – so then, “How do I read the first line?” asks Cherlin. As a result, “Different readings of the dash suggest different poetic rhythms, different subtleties of shading, accent and dynamics. Throughout, the grammatical markings of 1929 place uncalled-for liitations on interpretation.” I found Cherlin’s essay fascinating – and spot-on – as related to rhythm and accent; however, I think he neglected – or at least left unanswered – the role of melody and harmony – because I would be interested to hear his thoughts on Copland’s use of melody in “The World Feels Dusty” – and in Copland’s other movements as well. Read the lines of the poem. Do they suggest a rhythmic flow to you? If you were to sing this poem, do you hear specific intonations for the words? I’m not going to say that Copland “got it wrong” – on this or any of the other movements – because he composed it the way he heard it; but to me, the vocal lines of this song-cycle seem forced and unnatural. In an earlier post, I said the vocal line “ is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable.” I believe I even said “bloated” and “melodramatic” more than a couple of times – and alas, Cherlin never really addressed the important dimensions of melody and euphony when making music. Am I being overly critical of Copland's work? LOL. I did like the piano accompaniment. This post continues a discussion of the lyrics used by Aaron Copland in his 12-movement song-cycle, "The Poems of Emily Dickinson for Vocals and Piano." TO ACCESS PART 1, CLICK HERE. TO ACCESS PART 2, CLICK HERE. I’ve been discussing the lyrics Aaron Copland used in his 12-movement song-cycle “Poems by Emily Dickinson for Vocals and Piano.” His work premiered in 1950 – 5 years before Thomas Johnson’s seminal work from 1955, “The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson,” so Copland was using poems from very early publications where the publishers modified (and/or even omitted) Dickinson’s words, lines, stanzas and punctuation. I’ve covered movements 1 through 6 and 10, so today I have information on movements 7, 8, 9, 11, and 12. In movement 7, “Sleep is supposed to be,” there are no differences (except, perhaps, in punctuation), so Copland’s lyrics match the poem as it appears in Johnson’s compilation. In the 8th movement, “When they come back – if Blossoms do,” the 5th line of the poem reads “When they begin, if Robins may,” but Copland has “When they begin, if Robins do.” In line 10, the poem states, “Had nobody a pang,” while Coplands lyrics have “Has,” and in the poem, line 11 uses “lest,” but Copland uses “that.” Hmm…I could not find info as to an earlier version that had these modifications, but I suspect there must be one. I can’t imagine Copland made these small changes on a whim. For “I felt a funeral in my brain,” the 9th selection of Copland’s 12, the first four stanzas are exactly the same – EXCEPT – in line 3, Copland added an extra “treading” – and in line 7 he has an extra “beating” – but that could just be the liberty of a song-writer – it’s pretty typical to include repetition like that. However, he was using a version of the poem published in 1896, and the publisher comletely omitted the final – and morst eerie? Most important? – stanza. It reads like this: And then a Plank in Reason, broke, And I dropped down, and down – And hit a World, at every plunge, And Finished knowing – then – I have no idea why they made the decision to omit that entire stanza. For the most part, the song lyrics in the 11th movement, “Going to Heaven,” match the poem, although Copland repeats the line “Going to Heaven” several times at the beginning and at other times of the song. There are two other minor differences: In line 14, while the poem says “Save just a little space for me,” the song substitutes “place” for “space.” And in the 24th line, the poem uses the contraction “I’m,” while Copland uses “I am.” The “space/place” change seems to come from the 1891 version – though I’m not sure about the “I’m” vs. “I am.” For the final movement of his 12-song opus, Copland use the title, “The Chariot,” so that let me know right away that he used the poem from the 1890 edition of selected poems by Dickinson – for that was the title the publishers gave “Because I could not stop for death.” The lyrics are the exact same for the first two stanzas of the poem, but for the third stanza, 1890 version of the poem replaces “At Recess – in the ring” with “Their lessons scarcely done” – and then the early version (and hence the song) omits stanza 4 completely – it moves straight to the fifth stanza which replace “but a mound” for “in the ground,” and “But” in place of “And yet.” Interestingly, Copland marked this song at its start with the direction to play “with quiet grace.” LOL – I composed a song based on this poem, and I wrote my work in the style of a seductive tango. I suppose music, like art, is in the eye – or in this case, the ear – of the beholder. FOR PART 1 OF THIS DISCUSSION, CLICK HERE. 1. From January 23, 2024:I posted a link recently to Aaron Copland’s 12 movement song-cycle “The Poems of Emily Dickinson for Vocals and Piano.”

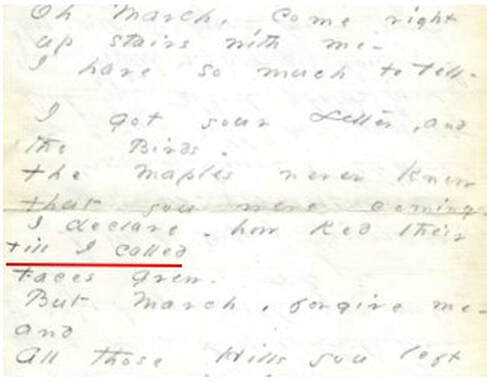

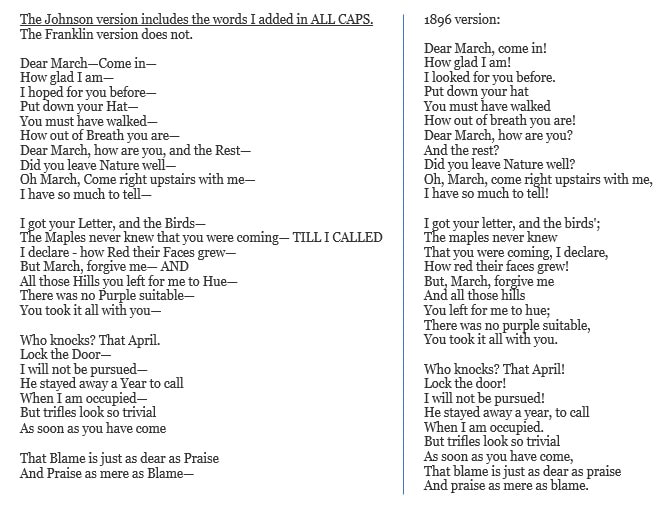

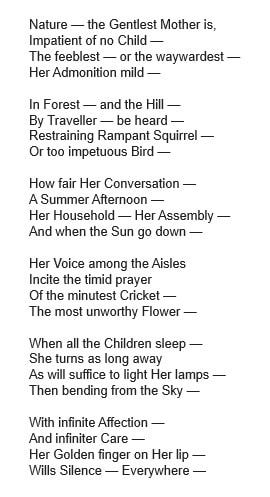

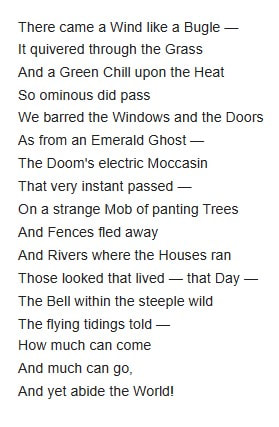

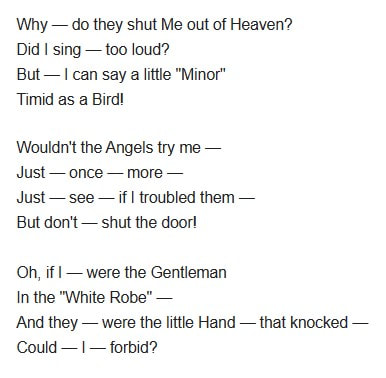

Why did I start with the 4th? Mainly due to a very interesting article I found about that specific poem by Dickinson and its corresponding song by Copland. I’ll get to that article soon (i.e. on some day in the near future – not in this post) to discuss various points made by author Michael Cherlin (including a further look at Dickinson’s use of dashes – a topic I hit on from 1/16 to 19). Today, I’ll provide a look at Copland’s lyrics for movements 1, 2, 3, and 5 from his work. In the first movement, based on Dickinson’s poem “Nature – the Gentlest Mother is,” Copland’s lyrics match the Johnson edition poem – EXCEPT – in the opening line, Copland does not include the word “is” – as he used a version of the poem as published in 1891 and the publishers at that time purposefully omitted the word. Also, in line 6, the musical score reads “By Traveller – is heard” – another change made in the 1891 version; however, the woman sings “By Traveller – be heard” as is written in the version published by Johson. In the second movement, “The Wind came like a bugle,” the poem in Johnson has line 12 as “Those looked that lived – that Day –” but Copland used, “the living looked that day.” This was another modification made by the publishers in the 1891 version of the poem. Also, line 14 in Johnson is “The flying tidings told,” but Copland used “The flying tidings whirled” – another change made by the publishers in 1891. Interestingly, in the performance I linked, the woman sings “told” even though Copland’s lyrics read “whirled.” In “Why do they shut me out of heaven,” the third movement, Copland’s lyrics match the poem in Johnson exactly; however, Copland repeats line 8, “But don’t shut the door,” and Line 12, “Could I forbid” – and then he also ends the song by repeating the poem’s opening two lines, “Why do they shut me out of heaven? / Did I sing too loud?” This type of repetition is a common practice of lyricists in songwriting. In “Heart, we will forget him,” the fifth movement of Copland’s work, Copland used a version of the poem from an 1896 edition of the poet’s works. Therefore, Copland uses these words as lyrics: When you have done pray tell me That I my thoughts may dim Haste – lest while you’re lagging I may remember him This stanza from the poem actually reads as follows: When you have done, pray tell me That I may straight begin! Haste! lest while you’re lagging I remember him! Interestingly, in the performance I linked, the lyrics appear as the lines Copland used; however, the woman actually sings the lines as they appear in the poem. I’ll pick up with Copland’s sixth movement tomorrow. 2. From January 24, 2024:I’ve been comparing the lyrics used by Aaron Copland in his 1950 work “The Poems of Emily Dickinson for Vocals and Piano” to the poems published in Thomas Johnson’s seminal work from 1955, “The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson.” In making the comparisons of Copland’s 12-movement song-cycle, I’ve found that he’s used poems from various editions of Dickinson’s poetry – from 1890, 1896, 1921 and more. As a result, Copland used poems from editions where publishers frequently modified the words and punctuation. Today I have info on the 6th movement, “Dear March, come in!” In Johnson’s version in his “Complete Poems,” the 12th line reads as follows: “The Maples never knew that you were coming — till I called”; however, Copland’s lyrics omits the “till I called” – likely because he selected the poem from an edition of Dickinson’s poems published in 1896. Interestingly, in R. W. Franklin’s updated publication of Dickinson’s “complete poems” in 1998, he too omitted the words “till I called” – and perhaps he (and the 1896 version) got it right, and Johnson got it wrong. I think you’ll see what I mean when you check out the pic of Dickinson’s handwriting below. Two lines of the poem in Johnson (lines 12 and 13) read like this:

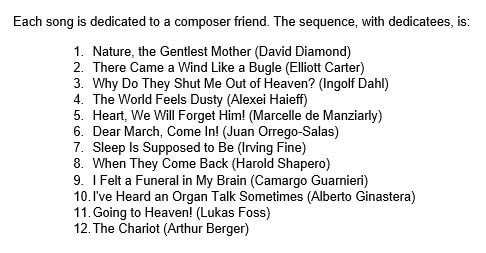

The Maples never knew that you were coming — till I called I declare — how Red their Faces grew -- But Dickinson’s handwriting says this: The Maples never knew that you were coming I declare – how Red their Till I called Faces grew – Sooo…Dickinson’s “Till I called” looks like a second thought/alternate possibility for “I declare” in line 13 – and NOT as an add-on segment of line 12. That’s why I think Franklin did not include “Till I called” – he went with her original thought, “I declare” in line 13 – and I’m a bit surprised that Johnson tacked the words on where he did. Of course, there could be some other version written by Dickinson that I’m not aware of? And then here’s another weird twist. While looking into the various versions of this poem, I stumbled upon a site (HERE) which discusses “Dear March, come in” specifically as used by Copland – and here’s what’s odd – the author included a copy of the poem “with Dickinson’s intended punctuation” – but the poem is missing lines 7 and 8. Did the blogger just make an error? Or is there a version out there without these lines? LOL – that’s the problem with researching Dickinson – there always seems to be “another version.” NOTE: When Melon Husk took over Twitter (now "X") and allowed for the proliferation of hate speech and misinformation, I deleted my account and began posting on Counter Social. On that platform, I publish a daily post about Emily Dickinson (using the hashtag #DickinsonDaily); the posts include Dickinson facts, trivia, info on her poems and letter, etc. Some recent posts focused on musical terms in Dickinson's poetry -- and some posts dealt with a song-cycle by Aaron Copland based on twelve poems by Emily Dickinson. Those posts are featured below. 1. From January 20, 2024:Earlier this month I posted info related to musical references in Dickinson’s poetry, and a couple of posts in mid-January highlighted the poem, “I’ve heard an organ talk, sometimes.” In one post I noted that American composer Aaron Copland had composed a song cycle of twelve works for voice and piano based on the poems Emily Dickinson, and it included “I’ve heard an organ talk, sometimes” (by the way, each song in the cycle was dedicated to a composer friend, and the entire sequence, with dedicatees, is shown in the picture below). To access and listen to Copland's work, click HERE. "Twelve Poems by Emily Dickinson for Voice and Piano" premiered at Columbia University in May 1950, with soloist Alice Howland accompanied by the composer. It was not especially well-received by critics, prompting Copland to note wryly to Leonard Bernstein, “I must have written a better cycle than I had realized.” Well, all jokes aside, I listened to the entire work yesterday, and I gotta say – Copland’s comment was not the case. The song cycle – particularly the vocal line – is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable. I did enjoy much of but not all of the piano line. For the most part, it was clever and, at times, evocative of the themes of the poems.

2. From January 21, 2024:Yesterday I posted the first part of a review of Aaron Copland’s 12-poem song cycle “The Poems of Emily Dickinson for Voice and Piano. I commented on the first three songs, and I figured I’d continue reviewing the other nine pieces today. Hmm…maybe that’s really not necessary. I opened yesterday’s post with the comment, “The song cycle – particularly the vocal line – is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable,” and then the reviews for the first three pieces were similar For the first work, I wrote, “I was not a fan, though, of the operatic intonations of the vocal line…. (it) sounded to me like something a neophyte song writer would compose because ‘that’s what a traditional art song sounds like.’” Concerning the second song, I wrote, “the vocals in the piece were just too overblown and melodramatic,” and for the third work I said that it was “sung in stereotypical ups and downs of stentorian, bloated and melodramatic tones.” I said that I’d provide additional reviews today – and I added a “spoiler alert,” that the reviews would not be that much different – so I think you get the picture. Was there anything I did enjoy about the song-cycle? I did enjoy much of the piano line. For the most part, it was clever and, at times, evocative of the themes of the poems. Hmm…let’s see. What else? We’ll be rooting for the Buffalo Bills tonight. My new son-in-law is from the Buffalo area, so we’re now rooting for his team! LOL – I’m being silly because I have nothing more to say about Copland’s forgettable opus. Really, there wasn’t a memorable song in the bunch. If interested, I’ll post some comments about songs 4 through 12 on my plog (poetry blog), and I’ll alert you when they’re ready. OH – I did have one other thought – and that is that Copland’s work premiered in 1950, five years before Johnson published his seminal edition of Dickinson’s “complete poems.” That makes me wonder where Copland got his versions of the poems he selected. I did check the three poems for the songs I reviewed yesterday, and they matched the lines in the Johnson edition. I’ll check for the other 9 poems today. Go Bills! 3. From January 22, 2024:So I made a bit of a goof – but working to correct that error has led me to a most interesting article! Here’s what happened: For the past two days, I’ve posted info on Aaron Copland’s “Twelve Poems by Emily Dickinson for Voice & Piano.” On the 20th, I gave short reviews of the first three pieces in the twelve-song work, and then then yesterday – rather than review the remaining nine songs, I just gave comments on the overall work – as critiquing the individual movements would have been like beating a dead horse. At the end of the post, I added this: “OH – I did have one other thought – and that is that Copland’s work premiered in 1950, five years before Johnson published his seminal edition of Dickinson’s ‘complete poems.’ That makes me wonder where Copland got his versions of the poems he selected. I did check the three poems for the songs I reviewed yesterday, and they matched the lines in the Johnson edition. I’ll check for the other 9 poems today.” Later in the day, though, I realized that I'd made a blunder, and I posted this: “I mentioned that Copland's work, from 1950, came out 5 years before Johnson's 1995 ‘complete poems,’ and I mentioned that -- for at least the first three songs in the work, Copland's versions of the poems matched Johnson's.But then I realized that I hadn't compared Copland's lyrics to the Johnson edition; instead, I had compared the versions of the poems I found online which I used to publish along with the post as I discussed the various pieces from Copland's song-cycle. Sooo...I'll go back to check Copland's lyrics as compared to Johnson's 1955 edition of Dickinson's ‘complete poems,’ and I'll let you know later how that turns out!” So that’s what I did. I compared Copland’s lyrics to the poems in the Johnson edition, and in doing so, I stumble upon a very interesting article about music, poetry, song-writing, and – in particular – the fourth movement of Copland’s song-cycle based on the poetry of Emily Dickinson, “The World Feels Dusty” – so let’s start there: For the most part, Copland’s lyrics do match Johnson – until you get to the last two lines. The song ends like this: “Dews are thyself to fetch and holy balms”; however, the poem in the Johnson edition ends like this: “And Hybla Balms / Dews of Thessaly, to fetch” (interestingly, those two lines are reversed in the Franklin edition of Dickinson’s poems). So why did Copland change those two lines? Well, in analyzing the poem, one site on Dickinson shrugged it off as this: “note that Copland changes "Thessaly" to "thyself" and "Hybla" to "Holy” as if Copland – on his own – just decided to alter the lines. However, I later found information that Copland had used a published version of the poem from 1929, and that version did include the modified lines – and that’s when I stumbled upon this article -- click HERE. Upon a first -- and fast -- read of the article, I found it to be fascinating -- so I plan to read it more thoroughly -- hopefully today (we'll see how busy I am. LOL). Sooo...more on this article -- AND -- more on the poems vs. the song-cycle by Copland in the coming days! TO CONTINUE TO PART 2 OF THIS DISCUSSION, CLICK HERE.

|

Archives

July 2024

PLOGA poetry log for the Emmett Lee Dickinson Museum (above the coin-op Laundromat on Dickinson Boulevard in historic Washerst, Pennsylvania). Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed