Some recent posts focused on music -- both in her life and in her poems -- and believe it or not, that series of posts even touched on the topic of sexual abuse!

Sooo...this will be a rather lengthy plog (poetry blog) post, covering 9 days of posts from Counter Social.

1. From January 7, 2024:

In May 1845 – when Dickinson was 14 – she wrote to her friend Abiah Root and said, “It seems almost an age since I have seen you, and it is indeed an age for friends to be separated. I was delighted to receive a paper from you, and I also was much pleased with the news it contained, especially that you are taking lessons on the 'piny,' as you always call it. But remember not to get on ahead of me. Father intends to have a piano very soon. How happy I shall be when I have one of my own!”

Later that year, she wrote to Abiah & said, “I never enjoyed myself more than I have this summer; for we have had such a delightful school and such pleasant teachers, and besides I have had a piano of my own. Our examination is to come off next week on Monday. I wish you could be here at that time. Why can't you come? If you will, you can come and practice on my piano as much as you wish to. I have been learning several beautiful pieces lately. The 'Grave of Bonaparte' is one, 'Lancers Quickstep,' and 'Maiden, weep no more,' which is a sweet little song. I wish much to see you and hear you play.”

2. From January 8, 2024:

In looking into this, I learned that (if I understand this correctly) in the mid- to late-1880s, people who were learning to play the piano would bind their sheet music in volumes; on the New York Public library website I found this – that “these books of bound sheet music were assembled primarily by women during their formative years of musical training...and Binders' volumes surveyed here in the (New York Public Library) Music Division and elsewhere, average out to approximately 35-45 pieces of sheet music per book.”

The music in Emily Dickinson's "binders' volume" was collected over a period of about eight years (ca. 1844–52), and – at just over 100 pieces – the Dickinson music book was uncommonly large.

Yesterday I posted copies of 3 pieces of Dickinson’s sheet music – titles which she mentioned in a letter to friend Abiah Root; however, not all of the song titles mentioned in Dickinson’s letters are in her bound music book – nor are they all part of the Dickinson Collection at Harvard. However, because the music cited by Dickinson was popular & widely collected at the time, the titles can be found in other NYPL collections in the Music Division.

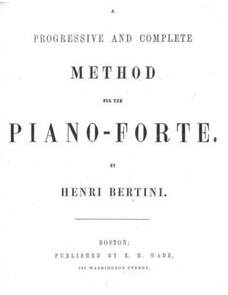

In the picture below of the Dickinson family’s piano, you can see on it Bertini’s “A Progressive and Complete Method for the Piano-Forte,” the common step-by-step lessons for learning the piano – and the method used by Emily Dickinson.

And yes – the “piano” was originally referred to as the “piano-forte” (or “forte-piano”).

The instrument, which was invented in 1698, could vary the sound volume of each note, depending on the player's touch; therefore, it was called the “piano-” (Italian for “soft”) “forte” (Italian for “loud”).

More on Dickinson and music tomorrow.

3. From January 9, 2024:

I found this info from the Music Division of the New York Public Library: “Of the sheet music titles in the Dickinson book, 35 percent contain a year of copyright. Another 30 percent can be dated by the plate numbers often included at the bottom of each page of music used by music publishers to identify and collate their yearly inventory. Nearly one third of the Dickinson music book’s content spans the years 1843–45, an active period of musical study for Dickinson (ages 12–14).”

And this: “Most binders from the period contain a majority of vocal music and only some instrumental numbers. In contrast, eighty percent of the Dickinson book is devoted to instrumental music indicating Emily’s keen engagement in the piano repertoire of her day.”

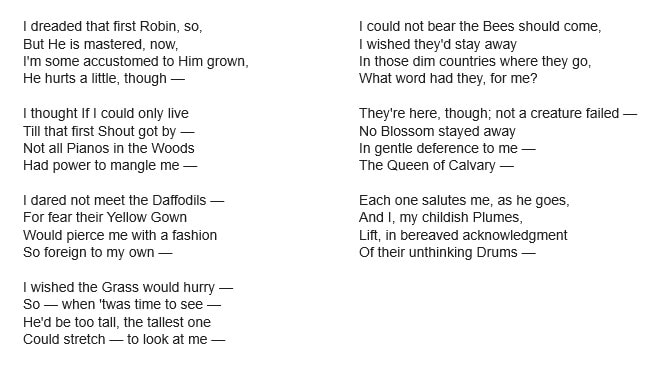

As “keen” as was her “engagement,” though, Dickinson used the word “piano” only once in her poetry; she used the plural “pianos” in “I dreaded that first Robin, so.” However, she used the word “music” in 20 different poems.

One of my favorite uses of the word “music” by Dickinson comes in the poem “This world is not conclusion." That poem opens like this:

This World is not Conclusion.

A Species stands beyond -

Invisible, as Music -

But positive, as Sound -

I’ll post the full poem – in its different versions – tomorrow.

4. From January 10, 2024:

Yesterday I posted the opening lines to the poem “This world is not conclusion” – with its hauntingly metaphysical image:

This World is not Conclusion.

A Species stands beyond -

Invisible, as Music -

But positive, as Sound -

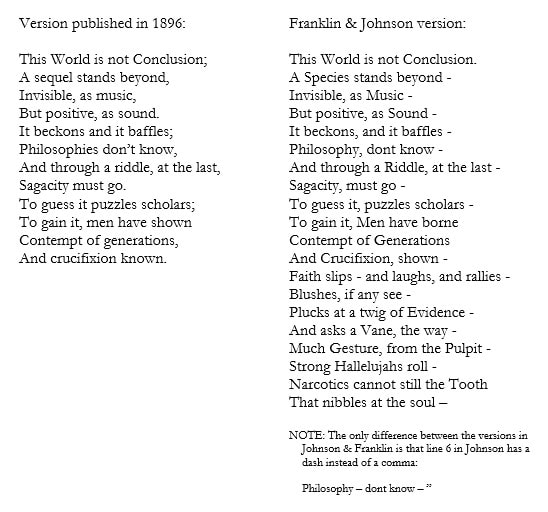

The poem as it was first published in the late 1890s was a 12-line poem. In the Johnson & Franklin editions of “complete poems” (1955 and 1998), "This world is not conclusion” appears with 20 lines.

Alternate word choices were also used in the early publication of the poem. For example, line 2 read “A sequel stands beyond” instead of “A species stands beyond” – and “species,” to me, is so much more memorable (and ominous).

Plus, in Line 12 of the early version, the poem concludes “And crucifixion known”; however, the longer versions say “And crucifixion shown” – & then the next line continues the thought: “Faith slips - and laughs, and rallies.“

Dickinson herself considered alternate word choices as well. In line 9, she considered “To prove it” instead of “To guess it.” In line 18, she considered “Sure” for “Strong.” In line 19 she considered “Mouse” for “Tooth.”

Interesting: I found this analysis of the poem from a site called “LitCharts.” I’d never seen this site before – and I didn’t access everything (I’m not sure if it’s all free or if there’s a charge), but I like the way that – when you scroll down – they color coded the lines and then provided a color coded “summary.” I could see this being helpful for students new to Dickinson.

More in-depth info is also provided further down the page – but much of it is blurred out unless you register (and pay? Again, I’m not sure if it’s free). To access the site, click HERE.

What do you think of this poem?

TBH, I’m not sure why the early publication chopped off the final eight lines. For ex: were those lines written on a separate piece of paper and then somehow got separated? The Dickinson archive did not include her handwritten draft of the poem so I’m not sure if that was the case or not.

5. From January 11, 2024:

What about other musical instruments?

The instrument Dickinson wrote about most often is -- a drum roll please -- the drum. “Drum” appears in 13 different poems.

“Trumpet” was used in 4 poems, “lute” was used in 4 poems, “violin” and “flute” both appeared in 3 poems, and “bass” was used in 2 poems (but not as the “string bass”; instead “bass” was used to represent a low-pitched, deep tone).

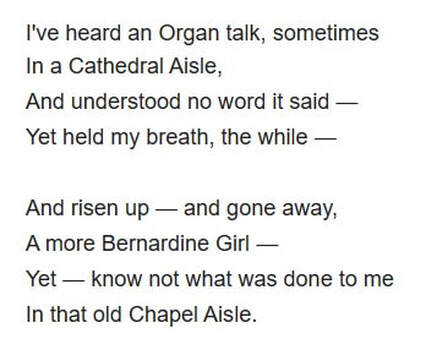

There were other instruments too. “Horn” was used in one poem as was “organ” and “guitar.”

“Coronet” was used in a single poem – but not as the trumpet-like instrument. “Harp” and “lyre” were never used.

I looked into the poem with “organ" (“I’ve heard an Organ talk, sometimes”) and loved it! The poem certainly reminded me of the opening lines from “There’s a certain slant of light”:

There's a certain Slant of light,

Winter Afternoons –

That oppresses, like the Heft

Of Cathedral Tunes –

When looking into this poem (“I’ve heard an Organ talk”) I stumbled upon some interesting – and strange – information! I’ll get to that tomorrow.

Also -- are there other instruments I should check for in Dickinson's poetry? Lemme know!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed