Some recent posts focused on musical terms in Dickinson's poetry -- and some posts dealt with a song-cycle by Aaron Copland based on twelve poems by Emily Dickinson. Those posts are featured below.

1. From January 20, 2024:

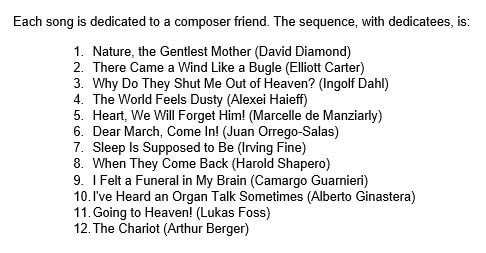

In one post I noted that American composer Aaron Copland had composed a song cycle of twelve works for voice and piano based on the poems Emily Dickinson, and it included “I’ve heard an organ talk, sometimes” (by the way, each song in the cycle was dedicated to a composer friend, and the entire sequence, with dedicatees, is shown in the picture below).

"Twelve Poems by Emily Dickinson for Voice and Piano" premiered at Columbia University in May 1950, with soloist Alice Howland accompanied by the composer. It was not especially well-received by critics, prompting Copland to note wryly to Leonard Bernstein, “I must have written a better cycle than I had realized.”

Well, all jokes aside, I listened to the entire work yesterday, and I gotta say – Copland’s comment was not the case. The song cycle – particularly the vocal line – is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable.

I did enjoy much of but not all of the piano line. For the most part, it was clever and, at times, evocative of the themes of the poems.

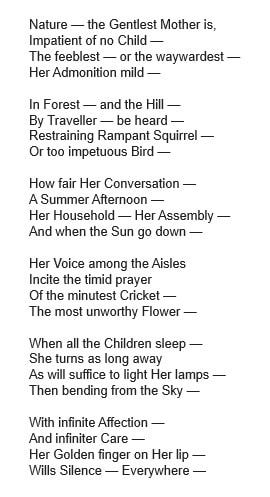

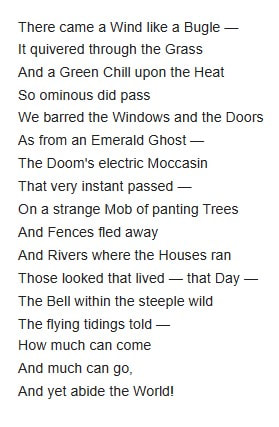

| For example, in the opening song, based on “Nature is the gentlest mother,” I loved the gentle and twittering bird-like opening notes. I was not a fan, though, of the operatic intonations of the vocal line. Personally, I would have composed something more lyrical – maybe even something along the lines of a lullaby? I did love much of the piano accompaniment, but the vocal line sounded to me like something a neophyte song writer would compose because “that’s what a traditional art song sounds like.” Ugh – it sounds more artsy-fartsy than even remotely artsy. The opening vocal line to the second song, “There came a wind like a bugle” is certainly depictive of the poem’s image of a blaring bugle, but again, I preferred the accompaniment; the vocals in the piece were just too overblown and melodramatic. |

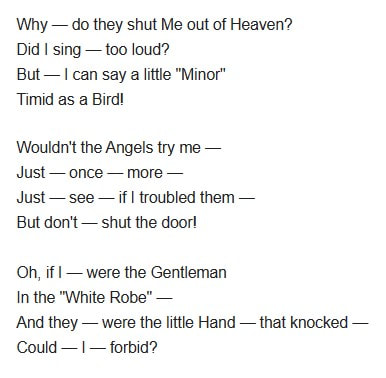

| I was not a fan of the third work either, “Why do they shut me out of heaven?” To me, this song – if not the entire 12-song cycle – sounded as though the composer were writing an opera libretto as if all speech in life – including recitations of poetry – was sung in opera-like fashion – and I don’t mean the lyrical arias or duets of the opera – but what would be the opera’s “spoken” dialogue — sung in stereotypical ups and downs of stentorian, bloated and melodramatic tones. I’ll provide additional reviews of the remaining songs tomorrow. Spoiler alert – the reviews won’t be much different from those I gave today. LOL. |

| Hmm…just an observation: I’d been talking about Dickinson’s use of dashes recently, and I noticed that two of the three poems posted today have high “dash to line” ratios. “Nature the gentlest mother is” has a little more than a dash per line, and “Why do they shut me out of heaven” has 18 dashes in 12 lines, or a 1.5 dash-to-line ratio. LOL |

2. From January 21, 2024:

Hmm…maybe that’s really not necessary. I opened yesterday’s post with the comment, “The song cycle – particularly the vocal line – is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable,” and then the reviews for the first three pieces were similar

For the first work, I wrote, “I was not a fan, though, of the operatic intonations of the vocal line…. (it) sounded to me like something a neophyte song writer would compose because ‘that’s what a traditional art song sounds like.’”

Concerning the second song, I wrote, “the vocals in the piece were just too overblown and melodramatic,” and for the third work I said that it was “sung in stereotypical ups and downs of stentorian, bloated and melodramatic tones.”

I said that I’d provide additional reviews today – and I added a “spoiler alert,” that the reviews would not be that much different – so I think you get the picture.

Was there anything I did enjoy about the song-cycle? I did enjoy much of the piano line. For the most part, it was clever and, at times, evocative of the themes of the poems.

Hmm…let’s see. What else?

We’ll be rooting for the Buffalo Bills tonight. My new son-in-law is from the Buffalo area, so we’re now rooting for his team!

LOL – I’m being silly because I have nothing more to say about Copland’s forgettable opus. Really, there wasn’t a memorable song in the bunch.

If interested, I’ll post some comments about songs 4 through 12 on my plog (poetry blog), and I’ll alert you when they’re ready.

OH – I did have one other thought – and that is that Copland’s work premiered in 1950, five years before Johnson published his seminal edition of Dickinson’s “complete poems.” That makes me wonder where Copland got his versions of the poems he selected. I did check the three poems for the songs I reviewed yesterday, and they matched the lines in the Johnson edition. I’ll check for the other 9 poems today.

Go Bills!

3. From January 22, 2024:

For the past two days, I’ve posted info on Aaron Copland’s “Twelve Poems by Emily Dickinson for Voice & Piano.” On the 20th, I gave short reviews of the first three pieces in the twelve-song work, and then then yesterday – rather than review the remaining nine songs, I just gave comments on the overall work – as critiquing the individual movements would have been like beating a dead horse.

At the end of the post, I added this:

“OH – I did have one other thought – and that is that Copland’s work premiered in 1950, five years before Johnson published his seminal edition of Dickinson’s ‘complete poems.’ That makes me wonder where Copland got his versions of the poems he selected. I did check the three poems for the songs I reviewed yesterday, and they matched the lines in the Johnson edition. I’ll check for the other 9 poems today.”

Later in the day, though, I realized that I'd made a blunder, and I posted this:

“I mentioned that Copland's work, from 1950, came out 5 years before Johnson's 1995 ‘complete poems,’ and I mentioned that -- for at least the first three songs in the work, Copland's versions of the poems matched Johnson's.But then I realized that I hadn't compared Copland's lyrics to the Johnson edition; instead, I had compared the versions of the poems I found online which I used to publish along with the post as I discussed the various pieces from Copland's song-cycle. Sooo...I'll go back to check Copland's lyrics as compared to Johnson's 1955 edition of Dickinson's ‘complete poems,’ and I'll let you know later how that turns out!”

So that’s what I did. I compared Copland’s lyrics to the poems in the Johnson edition, and in doing so, I stumble upon a very interesting article about music, poetry, song-writing, and – in particular – the fourth movement of Copland’s song-cycle based on the poetry of Emily Dickinson, “The World Feels Dusty” – so let’s start there:

For the most part, Copland’s lyrics do match Johnson – until you get to the last two lines. The song ends like this: “Dews are thyself to fetch and holy balms”; however, the poem in the Johnson edition ends like this: “And Hybla Balms / Dews of Thessaly, to fetch” (interestingly, those two lines are reversed in the Franklin edition of Dickinson’s poems).

So why did Copland change those two lines? Well, in analyzing the poem, one site on Dickinson shrugged it off as this: “note that Copland changes "Thessaly" to "thyself" and "Hybla" to "Holy” as if Copland – on his own – just decided to alter the lines. However, I later found information that Copland had used a published version of the poem from 1929, and that version did include the modified lines – and that’s when I stumbled upon this article -- click HERE.

Upon a first -- and fast -- read of the article, I found it to be fascinating -- so I plan to read it more thoroughly -- hopefully today (we'll see how busy I am. LOL).

Sooo...more on this article -- AND -- more on the poems vs. the song-cycle by Copland in the coming days!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed