While looking into this, I stumbled upon a very interesting article by Michael Cherlin that specifically focused on Copland’s 4th song, “The World Feels Dusty.” The article is HERE.

As one who writes songs based on the poetry of Dickinson (and other poets too), I found the article fascinating I were – and if I were to “boil it down,” the overall gist of the essay is reflected in this statement from page 64:

“Within the first stanza’s vocal part, Copland has projected a hierarchy of articulations that clearly represent the 1929 version of the text, and clearly obfuscate alternative readings suggested by the authentic version.”

In other words, Copland’s mastery and methods as a composer were influenced by – if not limited and/or determined by – the 1929 modifications and punctuation of the poem as made by the early publishers.

One point Cherlin makes more than once in his essay is that he is not judging Copland’s work because of this, Instead he focused on how the composer approached the work based on the version of the poem that was available from the 1929 publication.

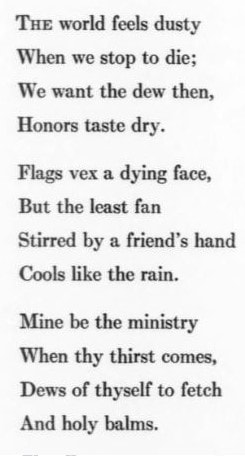

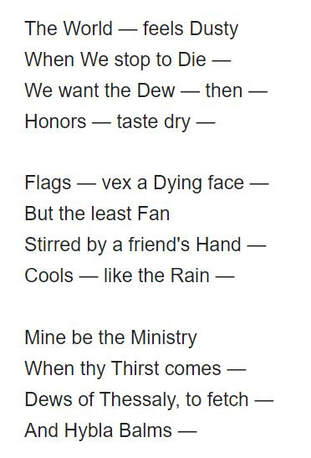

The pic below on the left is the version from 1929, published many times, including in the Atlantic Monthly (Volume 143), before the more authoritative version came out with the more characteristic punctuation, below on the right.

I love the analogies Cherlin makes in his opening paragraph of the songwriter approaching the poem – as an intruder, a gardener, or an interior designer – and he returns to a similar connection in his conclusion, the composer as some sort of aggressor: “Assailed at all sides, the poem is placed at the mercy of the composer’s whims.”

“Still,” he adds as he softens his anaolgy , “composers set poems that they love (to music), and love brings tender care.”

He then acknowledges that “good poems do not need the musical settings that composers bring. Likewise, music…does just fine without text.”

“When though, the match is well-made,” he concludes, “…the wedding of sound and sense creates new meaning for both. In creating new meaning we stand at the beginning.”

A Little More on the Topic from My CounterSocial Post on 1/28/24:

The gist of the article is that Copland’s craft as a composer was influenced by – if not limited and/or determined by – the 1929 modifications and punctuation of the poem as made by the early publishers.

Cherlin makes the point that a composer writing a song based on a poem will – obviously – focus on the rhythm and flow of the lines – but will also be driven by how he perceives the stress of syllables.

Consider the sentence, “I didn’t kick your dog.” One can interpret that line in one of five distinct ways:

I didn’t kick your dog.

I DIDN’T kick your dog.

I didn’t KICK your dog.

I didn’t kick YOUR dog.

I didn’t kick your DOG.

Back to the article on “The World Feels Dusty,” Cherlin said, “The different readings are different because of rhythm and accent, with accent properly understood as a subspecies of rhythm,” and “Most well-made poems play on multiple layerings of rhythm.”

Of course, based on that last statement, Copland was at a disadvantage because he was “fenced in” by the limitations of the punctuation set by the publishers of the 1929 version of “The World Feels Dusty.”

The actual poem includes – as Cherlin states – “the equivocal Dickinsonian dash, found in every line save two.”

As a result, the dash can “suggest a pause” – so then, “How do I read the first line?” asks Cherlin.

As a result, “Different readings of the dash suggest different poetic rhythms, different subtleties of shading, accent and dynamics. Throughout, the grammatical markings of 1929 place uncalled-for liitations on interpretation.”

I found Cherlin’s essay fascinating – and spot-on – as related to rhythm and accent; however, I think he neglected – or at least left unanswered – the role of melody and harmony – because I would be interested to hear his thoughts on Copland’s use of melody in “The World Feels Dusty” – and in Copland’s other movements as well.

Read the lines of the poem. Do they suggest a rhythmic flow to you? If you were to sing this poem, do you hear specific intonations for the words?

I’m not going to say that Copland “got it wrong” – on this or any of the other movements – because he composed it the way he heard it; but to me, the vocal lines of this song-cycle seem forced and unnatural.

In an earlier post, I said the vocal line “ is banal, cliched (in a predictabally over-blown operatic fashion), and not at all memorable.” I believe I even said “bloated” and “melodramatic” more than a couple of times – and alas, Cherlin never really addressed the important dimensions of melody and euphony when making music.

Am I being overly critical of Copland's work? LOL.

I did like the piano accompaniment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed